I remember watching the first space shuttle launch on TV. I was still a boy living at my parents’ house. The date was April 12, 1981 — and I was very excited.

I was holding my breath during liftoff. After Columbia had reached orbit and the TV station switched back to its normal programming, I stepped outside into our backyard. It was a warm and beautiful spring day, a blue sky broken up by gorgeous cumulus clouds.

Somewhere up there, I imagined, John Young and Robert Crippen would soon pass overhead. These guys were the epitome of coolness. For many years thereafter, I dreamed of being an astronaut or a top engineer launching rockets and spaceships to faraway places.

Today I was watching the shuttle’s last launch. No longer on TV, but via NASA’s media stream on the Internet. Imagine that! While the shuttle has hardly changed in three decades, the world has moved on profoundly.

Let’s face the truth. The shuttle demonstrated what was possible 30 years ago. If this still impresses you, I hope you are not working in today’s space program.

Cellphone inventor Marty Cooper introduced the mobile phone before the first shuttle flight. Are you impressed with it?

At its first launch, there was no World Wide Web. No live streaming. No digital social networks connecting people from all over the world. Hardly anyone had a computer. There were no cellphones, no digital cameras, no digital music downloads. No Internet chats and no video calls. You could not carry your entire music library with you. Or tens of thousands of images.

You could not simply pull up information when you needed it. I remember being fascinated with my first digital watch at about the same time. A miraculous new invention, the Compact Disc was introduced to the public in the same year.

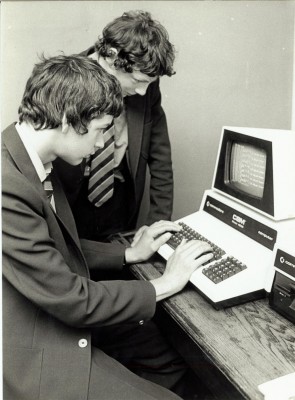

The hipsters using this computer before the shuttle's first flight must now be approaching retirement age. (I have a $20 watch with more computing power -- but shuttle operations did not get any cheaper).

For my generation, the most inspiring technological breakthroughs did not come from the space program, and certainly not from the space shuttle. Most of my generation looks at it as a 30-year old curiosity frozen in pre-historic times. Way before laptops and iPods. (The dark ages).

We will forever disagree on the question whether the shuttle was worthwhile or not. Personally, I don’t think so. I am not saying that the shuttle program lacked achievements — far from it. But I lament the greater achievements which would have been possible instead, for the same expense.

The program’s achilles heel wasn’t so much its cost in cash, but its cost on NASA culture. The complexity of the system, and its dangerous nature. This petrified NASA. Locked the agency and its subcontractors on an iron-clad course, which over the years became impossible to change. On this course, tens of thousands of highly qualified (and influential) people around the country built their entire careers. Many never did anything else — nor did they have to. Even today, it will be quite impossible to convince these armies of people that there may be better was of doing things.

WERNHER VON BRAUN WAS SHAFTED

I maintain that the biggest technological mistake the U.S. ever made with respect to space exploration was the sudden discontinuation of the Saturn system. Continued development of new Saturn variants (Wernher von Braun‘s team had plenty of ideas for this) would have achieved much more than the shuttle ever did.

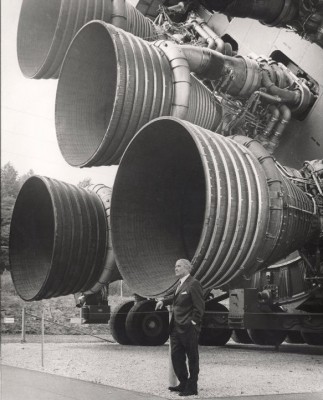

Wernher von Braun posing at the business end of the 1st stage of Saturn V. He knew all along that the shuttle concept NASA settled on was not a suitable replacement for the Saturn rockets. Von Braun's reservations and warnings were dismissed. Click to enlarge.

With the Saturn V, the space station, in its current configuration, would have been technically possible 20 years ago. If the U.S. had followed another crucial recommendation of von Braun’s team (the development of nuclear propulsion for deep space missions), we could have people on Mars right now.

We often hear that the Saturn system had become unaffordable after the moon landings. This argument amounts to circular logic. The only reasons why Saturn was discontinued: to free up funds for the shuttle’s development — and because of internal politics.

I strongly suspect that von Braun (and his Huntsville team) had become too powerful and influential for some people’s taste and personal ambitions. I will say it out loud: After the success of Apollo, von Braun was shafted. (For the complete story, see Michael J. Neufeld’s biography, Von Braun, Dreamer of Space / Engineer of War, ISBN978-0-307-26292-9).

NASA estimates that each shuttle launch costs about $450 million. However, Roger A. Pielke, Jr. has calculated that the Space Shuttle program has cost about $170 billion (2008 dollars) through early 2008. This works out to an average cost per flight of about US$1.5 billion.[1]

By comparison, a Saturn V launch would cost about $1.1 billion in today’s money.[2]

The difference? The shuttle can lift a payload of 24,400 kg into low Earth orbit. But one Saturn V could haul 118,000 kg. In other words, one Saturn V can launch the same mass as five shuttle flights! (Even more would have been possible with the future Saturn variants von Braun had on the drawing board).

Imagine the kind of space telescopes, Mars rovers and space stations that would have been possible with the Saturn rockets instead of the shuttle!

Today, of course, is the shuttle’s last hurrah, and we should not spoil the party. Even to me, the shuttle feels a bit like a childhood friend. The people who worked on it deserve respect.

After Columbia has safely returned to Earth, the orbiters should land at museums. And we, having long outgrown our childhood friends, should finally launch into the future.

Perhaps we should start by re-reading the papers Wernher von Braun’s team presented back then. Back in the dark ages.