Charles Lindbergh’s 122nd Birthday

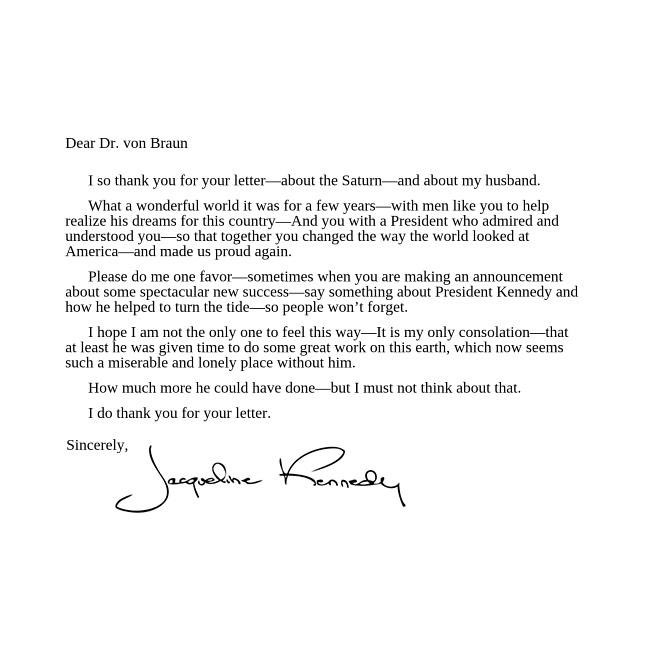

Born on February 4, 1902, Charles Augustus Lindbergh would be 122 years old today. Although mostly remembered as an aviator and U.S. military officer, he had a wide range of interests besides aviation – among them politics and international relations.

A prominent member and spokesman of the America First Committee, Lindbergh was strongly opposed to President Franklin Roosevelt’s foreign policy.

(Photo: Charles Lindbergh as a 25-year old, in 1927 – the year of his historical flight from New York to Paris).

Like many of his contemporaries, Lindbergh believed that Soviet communism was by far the greatest threat to America, and thus advocated a neutral stance toward the NSDAP’s rise in Germany.

This was indeed a very popular opinion among the American public at the time, and easily the majority. The way America had been drawn into World War 1 just a little more than two decades earlier played a major role in this.

Lindbergh later wrote:

“I was deeply concerned that the potentially gigantic power of America, guided by uninformed and impractical idealism, might crusade into Europe to destroy Hitler without realizing that Hitler’s destruction would lay Europe open to the rape, loot and barbarism of Soviet Russia’s forces, causing possibly the fatal wounding of Western civilization.“

Lindbergh died on August 26, 1974. During his life, he had witnessed both world wars (fighting for the U.S. in WW-2, albeit unofficially), the enormous rise of commercial aviation, the first nuclear weapons and the beginning of the nuclear age, the electronics revolution, the Cold War and the split of Europe into a free market Western part and a communist Eastern part, the Cold War’s proxy wars in Korea and Vietnam, the Cuban missile crisis, the culture wars of the 1960s, and the space race culminating in the first manned moon landings.

Almost 50 years have passed since Lindbergh’s death. Today’s world includes the Russian invasion of Ukraine, North Korean saber rattling against South Korea, the People’s Republic of China openly talking about (and practicing) the invasion of Taiwan, Iran’s nuclear ambitions, and the aftermath of the attack on Israeli civilians originating from the Gaza Strip — all of which could easily compound and escalate into a global conflict with the potential for nuclear weapons being used.

I often wonder how, if he was alive today, Charles Lindbergh would judge the contemporary geopolitical situation, and the state of America and Western Civilization, in 2024.

A Girl And Her Kitten

July 10, 1946: Daughter of Charles B. Lewis, miner, holding her kitten. She is seen here sitting in the kitchen of her home in a Union Pacific Coal Company housing project, Winton Mine, Winton, Sweetwater County, Wyoming. Photographer:

Lee, Russell, 1903-1986.

Soure: National Archives.

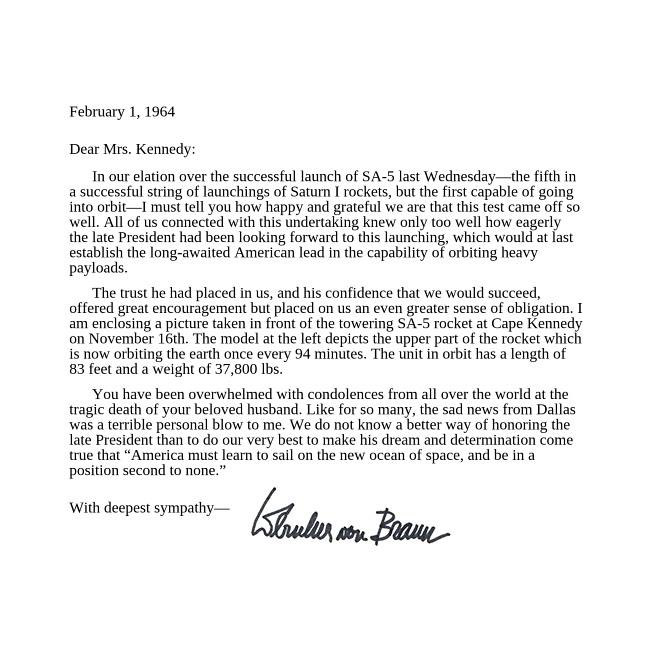

Werher von Braun’s Letter to Jacqueline Kennedy

Halloween 2023

All houses wherein men have lived and died

Are haunted houses. Through the open doors

The harmless phantoms on their errands glide,

With feet that make no sound upon the floors.

We meet them at the door-way, on the stair,

Along the passages they come and go,

Impalpable impressions on the air,

A sense of something moving to and fro.

There are more guests at table than the hosts

Invited; the illuminated hall

Is thronged with quiet, inoffensive ghosts,

As silent as the pictures on the wall.

The stranger at my fireside cannot see

The forms I see, nor hear the sounds I hear;

He but perceives what is; while unto me

All that has been is visible and clear.

We have no title-deeds to house or lands;

Owners and occupants of earlier dates

From graves forgotten stretch their dusty hands,

And hold in mortmain still their old estates.

The spirit-world around this world of sense

Floats like an atmosphere, and everywhere

Wafts through these earthly mists and vapours dense

A vital breath of more ethereal air.

Our little lives are kept in equipoise

By opposite attractions and desires;

The struggle of the instinct that enjoys,

And the more noble instinct that aspires.

These perturbations, this perpetual jar

Of earthly wants and aspirations high,

Come from the influence of an unseen star

An undiscovered planet in our sky.

And as the moon from some dark gate of cloud

Throws o’er the sea a floating bridge of light,

Across whose trembling planks our fancies crowd

Into the realm of mystery and night,—

So from the world of spirits there descends

A bridge of light, connecting it with this,

O’er whose unsteady floor, that sways and bends,

Wander our thoughts above the dark abyss.

(Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1807 – 1882)

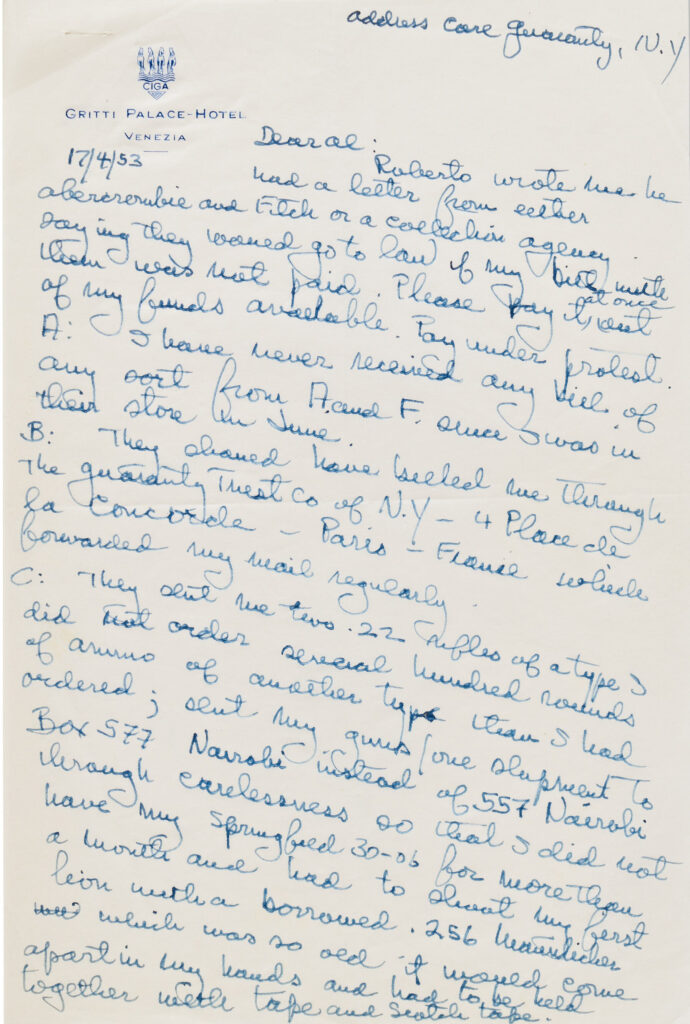

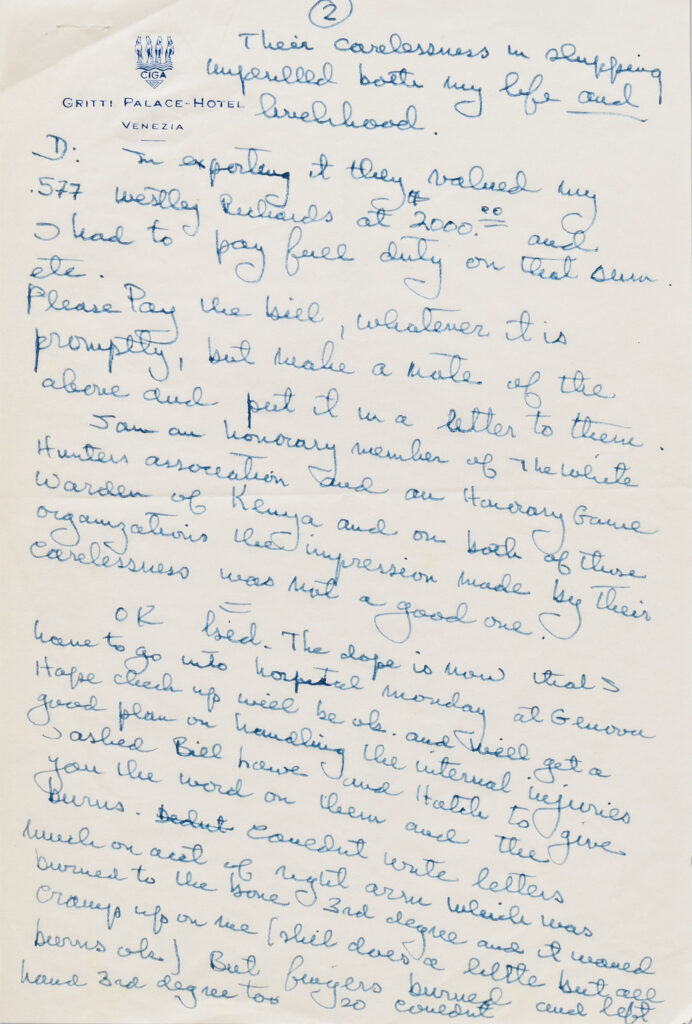

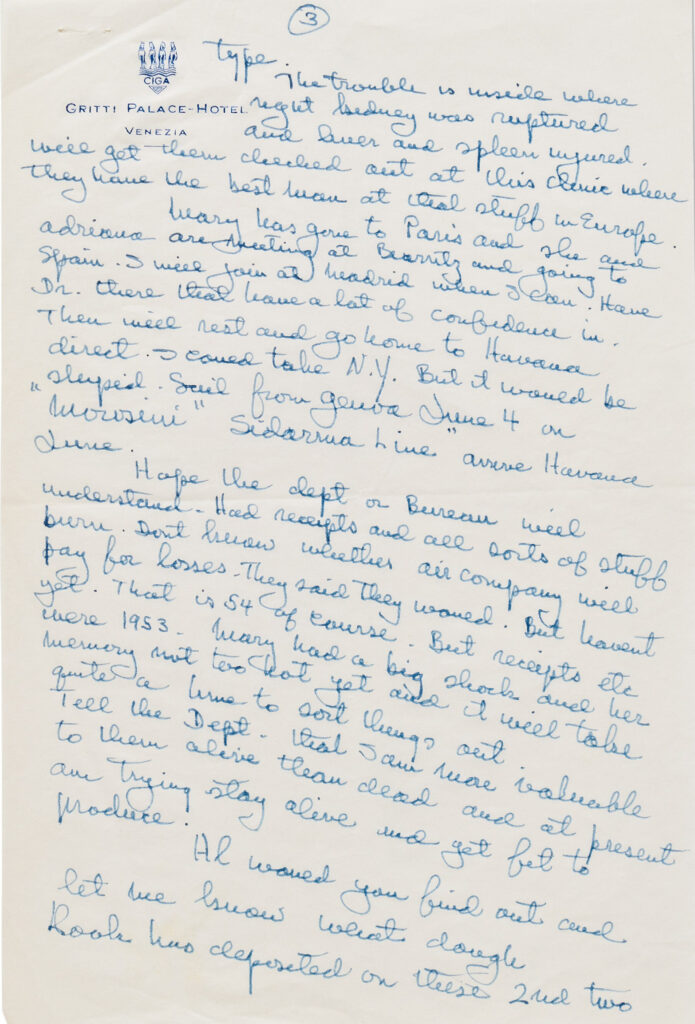

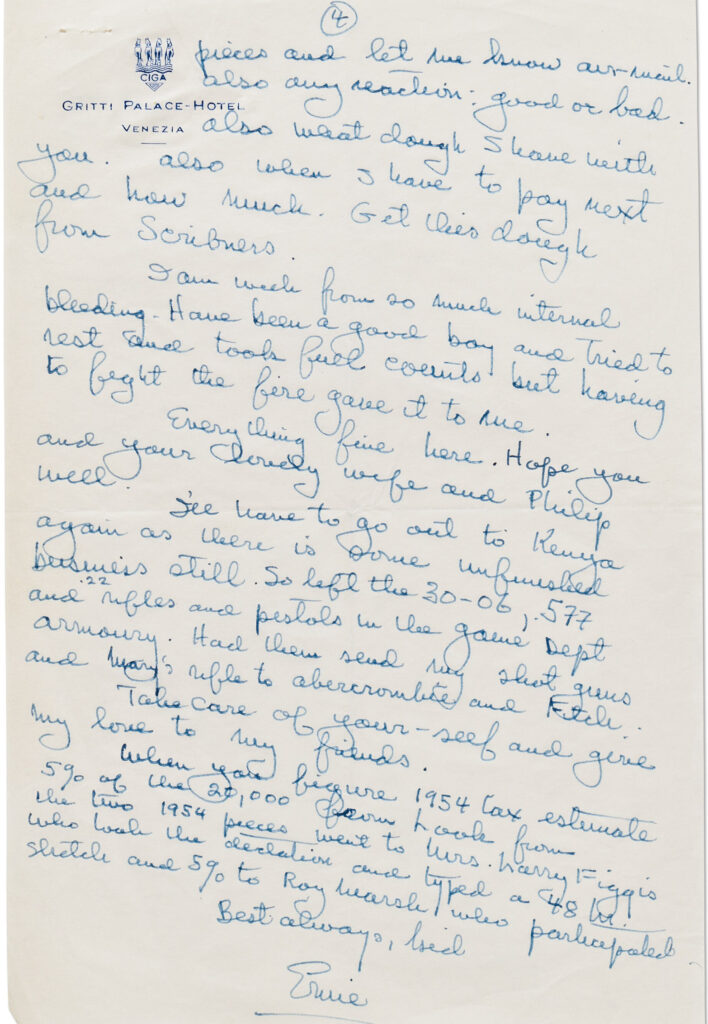

Ernest Hemingway Letter Reveals Toll Of Injuries

To say that Hemingway was prone to injurious brushes with death would be an understatement. In WW-1, he was nearly killed by a mortar blast in Italy. (He had just returned from the canteen and from bringing chocolate and cigarettes for the men at the front line). His shrapnel injuries sent him to the hospital for six months. Then, during WW-2, a German anti-tank round blew him from the sidecar of a motorbike, hurling his head into a rock. In a 1945 a car accident he “smashed his knee” and sustained another “deep wound on his forehead” (along with a concussion), which was followed by another car crash in 1947. And so it continues.

In January 1954, while in Africa, Hemingway was almost fatally injured in two successive plane crashes. During a flight over the Belgian Congo, the chartered plane struck a utility pole and went down in heavy brush. Hemingway’s injuries included a head wound. His wife Mary, also on board, broke two ribs. A pilot who passed over the wreckage spotted no survivors. A report went out saying the famous American author was dead.

In fact, Hemingway, his wife, and the pilot had escaped from the wreck and were camped in the brush nearby, surrounded by a herd of elephants, and eventually rescued by a tourist boat.

The next day, the couple boarded another plane to get medical care in Entebbe, Uganda. But the aircraft caught fire, crashing during take-off. In the second crash, and while escaping from the wreck, Hemingway suffered burns and yet another concussion, the head injury being serious enough to cause a leakage of cerebral fluid.

Hemingway made light of it when he and his wife finally arrived in Uganda (this time by car), carrying a bunch of bananas and a bottle of gin.

Despite suffering from his severe injuries, Hemingway proceeded to go on a fishing trip with his wife and son. This time he got caught in a brushfire. Again he was injured, sustaining second-degree burns on his lips, legs, front torso, left hand, and right forearm.

Months later in Venice, Italy, Hemingway’s wife recounted the extent of the damage to friends: two cracked discs, a kidney and liver rupture, a dislocated shoulder and a broken skull.

Now, a handwritten letter from Hemingway to his lawyer has re-surfaced, and was sold at Nate D Sanders Auctions in Los Angeles. Dated April 17, 1953 (which is an error – it was 1954), and written on paper from the Gritti Palace Hotel in Venice, Italy, Hemingway’s own writing gives a glimpse of the events as he saw them.

Apple Music Classical

I am excited about the upcoming Apple Music Classical app, due to be released at the end of this month.

Unlike regular Apple Music, the new app will feature indexing specific to classical music. This means users will be able to search for composers, periods, sub-genres as well as orchestras, conductors and specific performances.

But there is more: Apppe Music Classical promises more fairness toward classical musicians. Under the existing model, streaming royalties are paid per play. Here’s what this amounts to:

Consider the production costs of a cheaply whipped out, primitive and formulaic 2-minute pop song produced from computer software, and without any formal musical training.

Now consider the costs for recording a whole orchestra consisting of musicians with decades of training, playing a whole symphony in a large venue or studio, with very expensive instruments, and it’s all recorded and mixed with expensive equipment and in complex setups requiring a large group of audio technicians.

These two examples incur very different production costs. And yet, under the current streaming model, both of the examples mentioned above are yielding the same payout per play. This was never fair.

Details have not been released at this time, but it is presumed that Apple Music Classical will pay royalties not only per play, but also by listening time, and perhaps even other factors. For example, I would hope that a full orchestra or opera company would get higher royalties than a chamber orchestra or a small ensemble. Time will tell.

Use of the app is included with existing Apple Music subscriptions. Apple Music Classical can already be pre-ordered at the App Store.

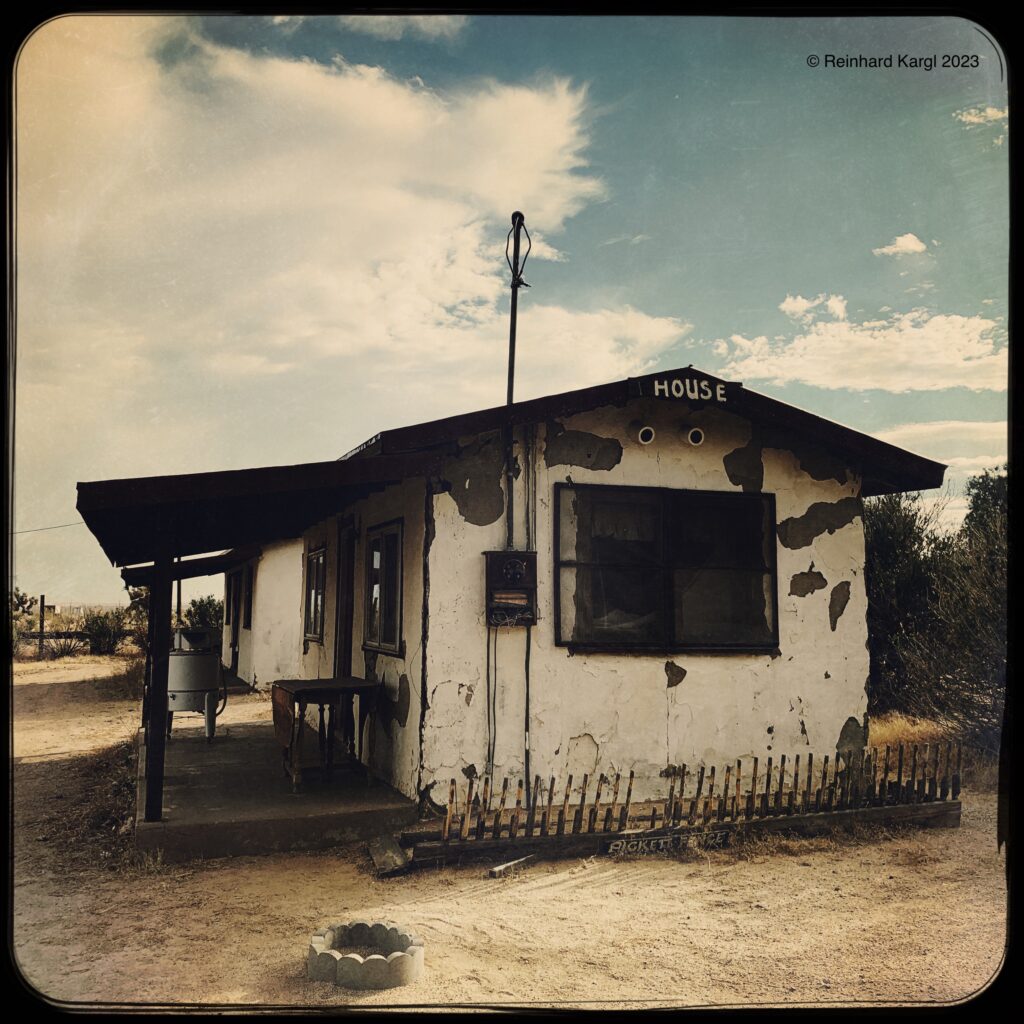

Halloween 2022

Layers of gas and dust are the centerpiece of this view of the Pillars of Creation taken by Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument. Thousands of stars exist in this region – 6,500 light-years from Earth – but are not visible in the image since stars typically do not emit much mid-infrared light. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Alyssa Pagan (STScI) Full Image Details

Street Lights

Here’s a picture of 6th Street (between Olive Street and Flower Street) in Downtown Los Angeles, 1930. It was part of this article about the history of street lights in Los Angeles.