by Reinhard Kargl

Commerce has tricked many people into believing that Christmas begins with Black Friday sales.

Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. The four weeks before Christmas are called “Advent”. Thereafter, Christmas begins with Holy Night (the night from December 24th to December 25th). Or does it?

Well, if you really love Christmas, you may actually enjoy it three (or even four) times. How come?

First of all, there are no historical records of the birth date of Jesus of Nazareth. So the chosen date for celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ was picked rather arbitrarily. However, it stands to reason that the date was chosen to coincide (roughly) with winter solstice. This natural event had been a sacred day ever since human civilization grasped the rudimentary fundamentals of celestial cycles. The Romans (as well as many other literate cultures) had of course more than just a basic understanding of this.

By the way, contrary to popular belief, Christmas is not the most important holiday in Christianity, nor was it even celebrated in the early beginnings.

In 330 AD, the Roman Empire split into two parts: the western half centered in Rome, and the eastern half centered in Constantinople. The churches of the Western Roman Empire continued to celebrate Christmas as a minor holiday on December 25.

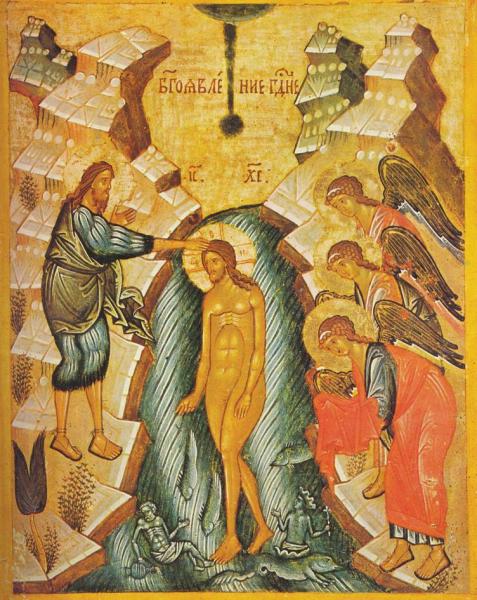

But in the East, the birth of Jesus began to be celebrated in connection with the Epiphany, on January 6. This holiday was not primarily about the the birth of Jesus, but rather his baptism. The feast was introduced in Constantinople in 379, in Antioch towards the end of the fourth century ( probably in 388) and in Alexandria in the following century.

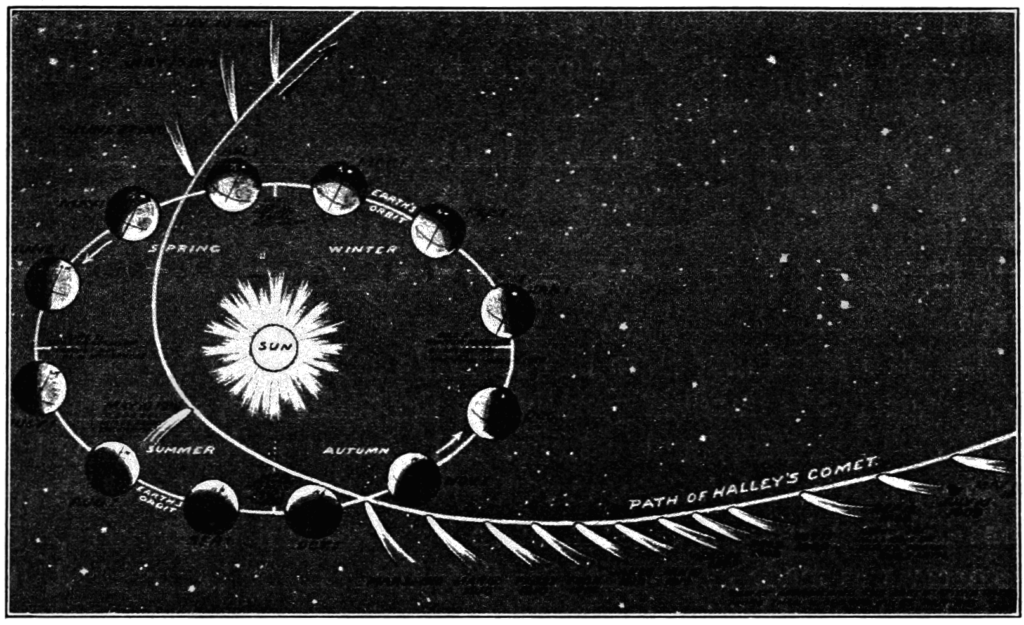

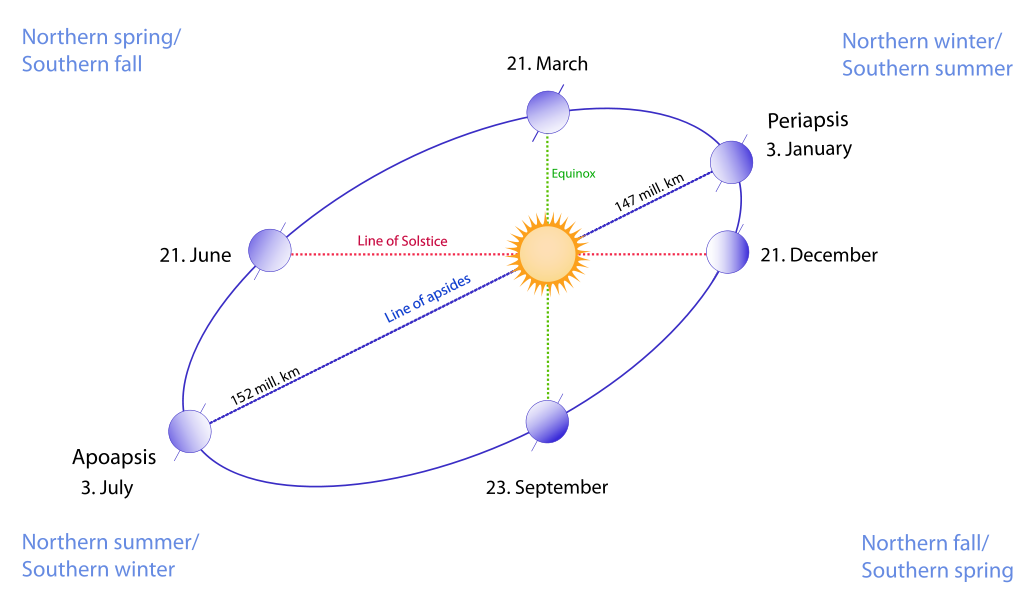

When it comes to marking days, all conventional, numerical calendar systems suffer from an astronomical problem: During the time it takes for the Earth to complete one full orbit around the Sun, our planet rotates 365.256 times around its own axis. What this means is that the day isn’t really 24 hours long. Earth spins once in about 24 hours with respect to the Sun, but once every 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds with respect to other, distant, stars.

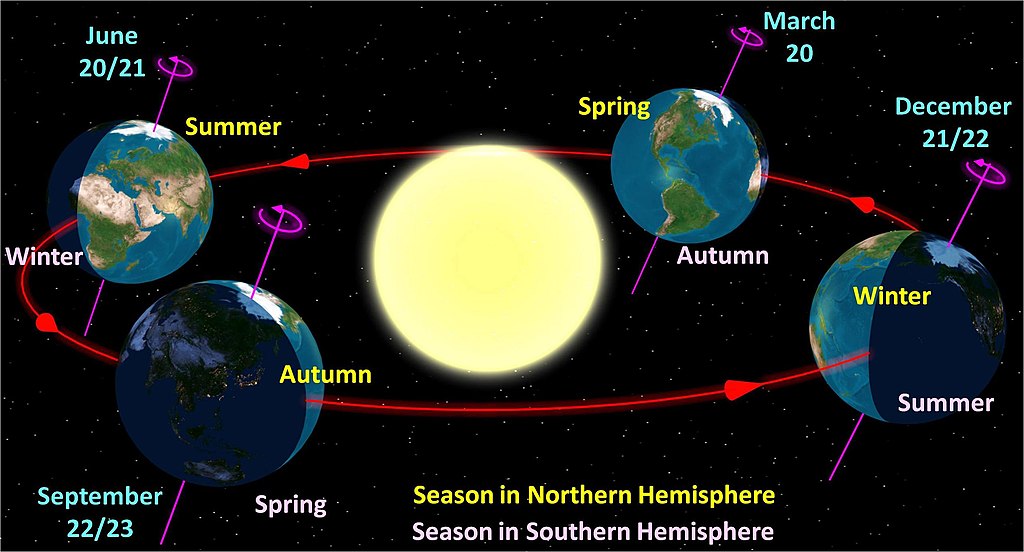

So one Earth year isn’t 365 days long, but precisely 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes and 46 seconds. How does one put that into a calendar when we define each 24-hour period as a “day”? And when we divide the year into 12 months – which, by the way, are all arbitrary, man-made definitions? There really are are only four natural demarkations in the year that play a major role in our lives: the two equinoxes and the two solstices, which mark the beginnings of each season.

For completeness, because Earth’s orbit isn’t a circle but an ellipsis, there are the two apsides, the two extreme points of Earth distance to the Sun: Aphelion (apoapsis) and perihelion (periapsis). But these two would have little to no practical effect except for those studying such things.

The Julian Calendar, was proposed by Julius Caesar in 46 BC and enacted by edict on January 1, 45 BC. No, Julius did’t invent it. It was a reform of an earlier Roman calendar and probably designed by Greek mathematicians and Greek astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandria.

Whoever did it, the Julian Calendar was undoubtedly one of mankind’s most remarkable intellectual accomplishments. But as all human explanations of natural phenomena, it is rather imperfect in that although its synchronization with the solar year is better than most other calendars, the deviations get bigger and bigger as time goes on. Eventually, the year’s four seasons and the calendar will become way off.

One can correct these deviations from the natural world by throwing in “leap time” – a strange concept in which we are basically making up days, months or even years. (In other words, we are violating the rules of science by purposely making our interpretation of the reality fit the observation).

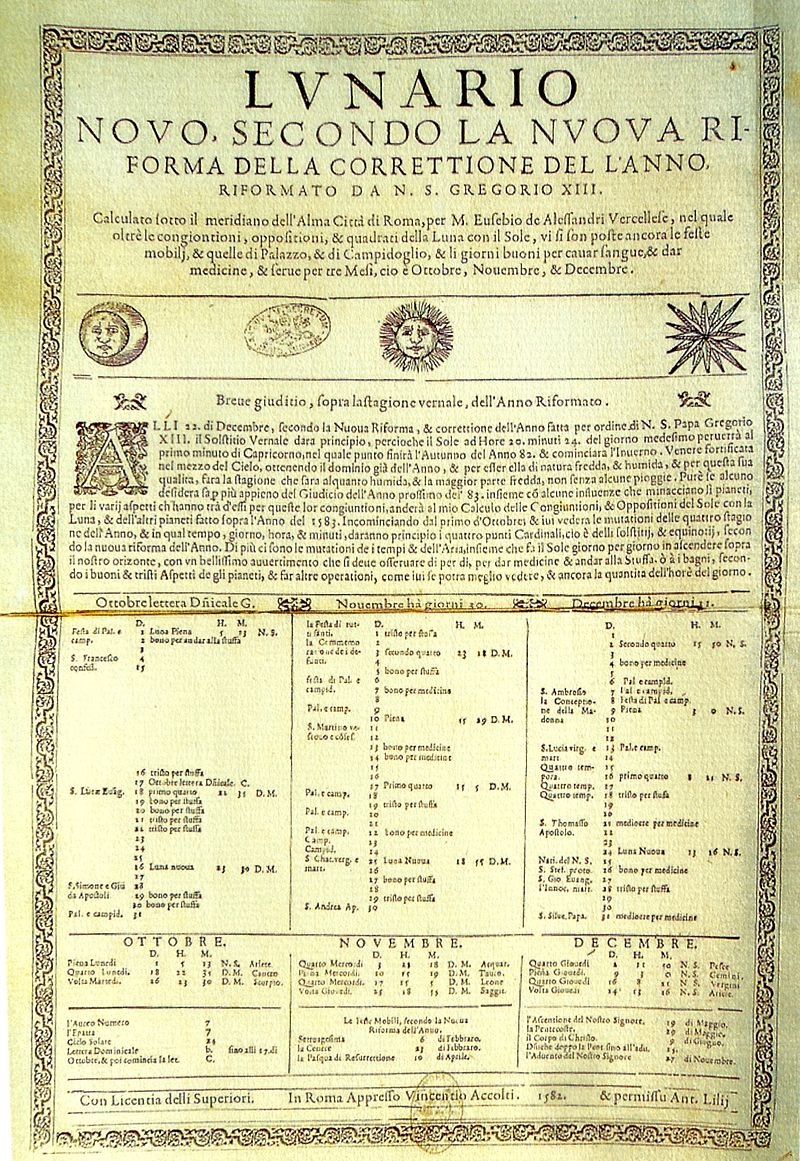

In order to reduce the need for such calendar doctoring, Pope Gregory XIII in October 1582 introduced the Gregorian calendar as a correction of the Julian calendar.

This has liturgical significance since calculation of the date of Easter assumes that spring equinox in the Northern Hemisphere occurs on March. To correct the accumulated error, Pope Gregory ordained the date be advanced by ten days. (One can do that is one is pope).

Most Roman Catholic lands adopted the new calendar immediately. (Not that they had much of a choice). The clerical leaders of Protestant lands who did not recognize the pope’s authority of course protested. But eventually, they too ended up following suit over the following 200 years. (Not because Protestants admitted the pope’s new calendar was a good innovation, but because having two different calendars caused quite a bit of confusion. Let’s just say it wasn’t popular with the masses).

The British Empire (including the American colonies) adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1752 with the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750. At that time, the divergence between the two systems had grown to eleven days.

This meant that Christmas Day on December 25 (“New Style”) was eleven days earlier than it would have been but for the Act, making “Old Christmas” (“Old Style”) on December 25 happen on January 5 (“New Style”).

In February 1800, the Julian calendar had yet another leap year but the Gregorian calendar did not. This moved Old Christmas to 6 January (“New Style”), which coincided with the Feast of the Epiphany.

For this reason, in some parts of the world, the Feast of the Epiphany, which is traditionally observed on 6 January, is sometimes referred to as “Old Christmas” or “Old Christmas Day”.

So where do we stand today? According to the Gregorian calendar, Western Christianity and part of the Eastern churches celebrate Christmas on December 25.

The Armenian Apostolic Church, the Armenian Evangelical Church, and some Anabaptists (such as the Amish people) still celebrate “Old Christmas Day” on January 6.

Meanwhile, most Oriental Orthodox and part of the Eastern Orthodox churches celebrate on January 7 (which corresponds to “Old Style” December 25).

Lastly, the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem maintains the traditional Armenian custom of celebrating the birth of Christ on the same day as Theophany (January 6), but it uses the Julian calendar for the determination of that date. As a result, this church celebrates “Christmas” (actually, Theophany) on what the majority of the world now considers to be January 19 on its Gregorian calendar.

So there you have it! The dates of Christmas are neither prescribed by God nor nature, but by man. They are nothing but human convention, and they differ because of the problems inherent in making a calendar that accurately reflects nature, along with some religious differences. Celebrate as you wish!

Merry Christmas.