Saturn V, SpaceX Starship, Space Shuttle (with external tank and solid rocket boosters).

SpaceX Starship, Tesla Cybertruck, human figure, SpaceX CrewDragon, Space Shuttle.

Much of the public debate about AI has focused on the often bizarre errors and biases in AI-compiled facts and figures. But there is another, perhaps more sinister danger: we are now entering a new era in which photographic evidence can no longer be trusted.

Here is an example:

Of course, the “1963 Mercedes 600 Pullman” never existed. Obvious mistakes (such as the nonsensical air vent and the missing hinge gap on the door’s lower section) make it easy to tell that this is just a rendering. And yet, most social media commenters were tricked into believing that this was a classic vehicle.

Given the rapid pace of development, obvious mistakes in AI-generated photographs will soon disappear. Soon it will be impossible to tell that a photograph or video was made up in a computer.

People have been conditioned to believe what they “see with their own eyes”. It is time to stop doing that.

I am excited about the upcoming Apple Music Classical app, due to be released at the end of this month.

Unlike regular Apple Music, the new app will feature indexing specific to classical music. This means users will be able to search for composers, periods, sub-genres as well as orchestras, conductors and specific performances.

But there is more: Apppe Music Classical promises more fairness toward classical musicians. Under the existing model, streaming royalties are paid per play. Here’s what this amounts to:

Consider the production costs of a cheaply whipped out, primitive and formulaic 2-minute pop song produced from computer software, and without any formal musical training.

Now consider the costs for recording a whole orchestra consisting of musicians with decades of training, playing a whole symphony in a large venue or studio, with very expensive instruments, and it’s all recorded and mixed with expensive equipment and in complex setups requiring a large group of audio technicians.

These two examples incur very different production costs. And yet, under the current streaming model, both of the examples mentioned above are yielding the same payout per play. This was never fair.

Details have not been released at this time, but it is presumed that Apple Music Classical will pay royalties not only per play, but also by listening time, and perhaps even other factors. For example, I would hope that a full orchestra or opera company would get higher royalties than a chamber orchestra or a small ensemble. Time will tell.

Use of the app is included with existing Apple Music subscriptions. Apple Music Classical can already be pre-ordered at the App Store.

North Carolina-based Blue Force Technologies, a composite aerostructures maker and Boeing supplier, is proposing UAVs which can mimic “the electronic signature, performance and tactics of Chinese or Russian 5th generation J-20 or Su-50 fighters”, according to a recent article in Forbes.com.

Named “Fury”, the purpose of the firm’s design study is to provide a much cheaper training aid for aircrews practicing intercept maneuvers against the latest generation of Russian and Chinese fighter jets. To accomplish this, the Fury UAV will “look, act and smell” like the real thing – at least beyond visual range. The advantage, compared to conventional training against manned aircraft representing the enemy is much lower cost. Many of the Fury parts, including the jet engine, can be sourced from existing, commercial production lines and off-the-shelf parts.

While the advantages for training purposes are obvious, I believe this technology can easily be adapted for another purpose. If drones can be built to simulate enemy fighters to on-board radars, and ground or air based early warning systems, then such drones can also be configured to mimic an F-16, F-15, F-22 or F-35, for example. And this would make it possible to use these UAVs as decoys. They could be sent into contested airspace for the purpose of triggering the enemy’s air defense systems.

Once these UAVs are “lit up” by enemy radar and the adversary launches surface-to-air missiles, the locations of mobile radars and mobile missile launchers are much easier to detect. They can be immediately targeted before the enemy can reposition them. Even if such a counterattack is not successful, the enemy will at least have used up some of his surface-to-air missiles to shoot down relatively low-cost drones.

If the technology works and large-scale production can bring down the cost, the introduction of large numbers of such decoy drones into a contested airspace could thoroughly confuse and disrupt hostile air defenses. Concealed among many decoy drones, the “real items” would be ready to strike the enemy’s air defenses while they are distracted and triggered by the decoys.

This is an emerging defense technology worth keeping an eye on.

I believe Apple’s latest introduction, the iPhone X represents a technological turning point. It’s not so much the phone itself, but the underlying technologies behind it that are truly groundbreaking. Ushered in with the iPhone X, their widespread adoption will have consequences far beyond mobile phones. Here are five reasons:

Face recognition technologies are available from others, but what Apple has come up with leaves everything else in the dust. This goes far beyond taking a photo and comparing it to a stored image. Apple’s Face ID technology projects invisible dots (in the current version: 30,000 of them) on the user’s face. It then uses stereoscopic viewing from two cameras to essentially create a 3-D map of the user’s face. No special lighting is necessary. In fact, because of IR illumination, this works even in the dark. What’s remarkable is not only the small size of this system, but also that it works fluidly. It is capable of capturing facial expressions in real time. Mapping and processing are so rapid that the data stream can be used to animate virtual characters, as Apple demonstrated with its animated emojis and mask overlays.

The point is that artists and developers will be able to apply this technology in new ways: the iPhone X is the first affordable, portable motion capture device for special effects. Since the mapping process works in real time, making fantasy characters talk and show facial expressions will be as easy as talking to the phone. This could mean: animated virtual announcers, talking heads and fictional characters for advertising, music videos, entertainment and perhaps even drama. Animating cartoons, which took many hand drawings by skilled animators in Walt Disney’s days, has become child’s play. Another application could be video games. Multi-player gamers could adopt fictional characters whose speech and facial expressions mimic the real player’s face, but expressed on the virtual character.

A mere expansion of the technology’s capabilities might make it possible to turn the iPhone X into a fully fledged 3-D body scanner or even a motion capture device. Imagine this: put the device on a stand and walk in front of it in the nude. Now turn around by 360º, and let the iPhone capture a 3-D scan of your body. Again, the data set could be used to bring fictional characters to life, but it could also be used for online shopping. No more need to try on clothes in a store! You could simply get a 3-D simulation of yourself wearing the clothes you are considering. Finding the right size would be automatic. Or people could simulate the look of make-up, jewelry or hairstyles.

Another conceivable application of face mapping technology might be improved speech recognition, for instance in a noise environment. Like a human lip reader, the technology would decode facial expressions to improve the legibility of spoken language. Those hard of hearing might even be able to use the phone as an artificial lip reader.

Battery capacity is still an achilles heel of mobile devices. Right now, incompatible charging devices and cables mean that we all got into the habit of charging our devices overnight, with chargers we own. Or we carry cables, chargers or external batteries.

What if you could simply “top off” your battery almost everywhere you go? The wireless charging technology Apple demonstrated works on all mobile Apple devices, such as iPhones, the AppleWatch and EarPods.

What Apple is pushing for is a truly universal standard. It would charge all mobile devices, of all manufacturers. This would mean: no more personal chargers are necessary. Everyone could simply use shared wireless “charge pads” located in homes, vehicles, workplaces or public venues. Businesses could either provide charge pads for a fee or allow their free use as a means of attracting customers.

In a radical departure, the iPhone X does away with one of the original iPhone’s key features: the “home” button. Apple wants to get away from buttons and ports for one main reason: these are incredibly difficult to insulate from dirt, water and dust. By eliminating all points of entry, water and dirt resistance will become the new standard.

Organic Light Emitting Diode displays have major advantages, but also some disadvantages. Apple’s new OLED iPhone X display (which interestingly is made by Apple’s prime competitor, Samsung) is an industry-first when it comes to size and quality. And it promises to have overcome the known OLED disadvantages.

The last remaining problem is the price: OLED displays are still much more expensive than traditional LED screens, which explains the whopping price tag of the iPhone X. But Apple’s hardcore fans are early adopters almost regardless of cost. And this might give Apple enough sales volume to create a breakthrough opening for OLED technology. In addition to the cost reduction by volume, there are emerging manufacturing technologies (such as printing and roll-to-roll vapor-deposition). When scaled up, these could significantly reduce OLED costs. In a few years, all mobile device makers might offer OLED displays.

With its vastly improved processing speed and wireless capabilities, the iPhone X can offload an increasing amount of data onto the cloud. Already, some features of the upcoming iOS 11 are hinting where we are going with this. In iOS 11, rarely used apps and data, and even iMessages and their attachments are no longer stored on the device but on iCloud, from where they can be retrieved if needed. We can expect this trend to accelerate.

In addition, the new faster WiFi and “short-link” radio technology (Bluetooth) processing would enable new capabilities such as wireless screen sharing, or the use of the iPhone X as a remote microphone or camera.

And of course, enhanced access to distributed grid computing makes digital voice assistants like Apple’s Siri steadily more powerful. Siri is already becoming increasingly contextual, and I would expect this trend not only to continue, but also for Siri to become more visual as well. For example, a hearing impaired user might point the iPhone X at a written text and have Siri read it aloud. Or, users might be able to point the camera at a tree and ask Siri: “What kind of tree is this?”

All in all, although the outside of the iPhone X does not look radically different from the original iPhone, the technology inside represents a quantum leap compared to what was possible only 10 years ago.

Vertically landing rockets have been a staple in science fiction for a long time:

And in the 1960s, Wernher von Braun’s Saturn team was already intensely thinking about outfitting future versions of the Saturn V with reusable stages. Among the many concepts studied were a winged flyback version and a parachute-assisted return. Unfortunately, these ambitions never went beyond the drawing stages. While closing down the Apollo program, NASA made the fateful (and as we now know, mistaken) decision to pursue the Space Shuttle as NASA’s exclusive launch vehicle. The vehemently protesting Wernher on Braun was sidelined and “kicked up” into a senior administrative position with little real decision making power. (Disappointed and unsatisfied, he left NASA a few years later). Since then, astronauts have been confined to low Earth orbit, going essentially nowhere but in circles.

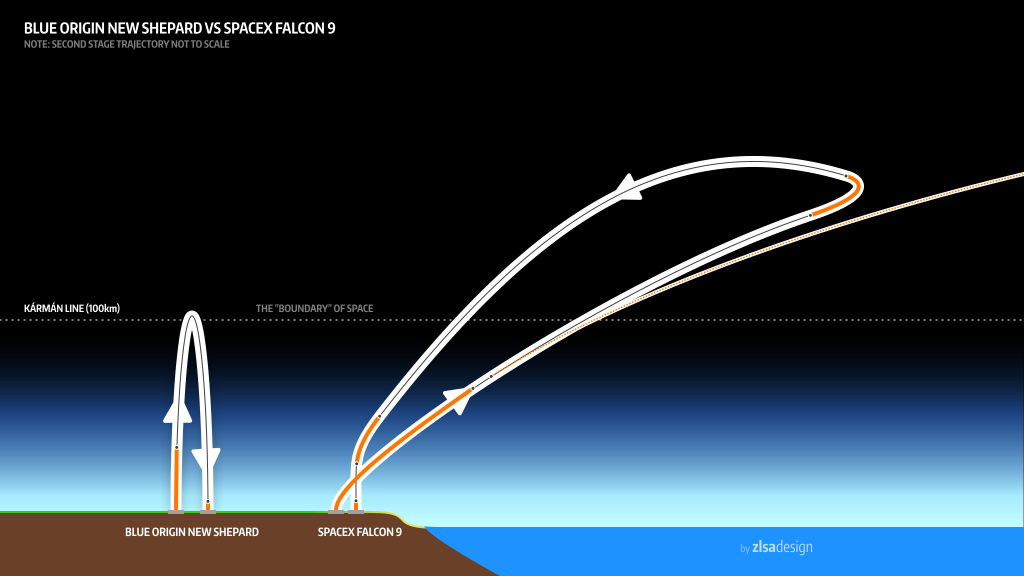

It took almost five decades for the reusable rocket concept to return and become reality, and it was neither NASA nor any other national space program, but two private companies which accomplished the first proof-of-concept.

In November 2015, Blue Origin had successfully landed an experimental test rocket at its launch site in West Texas. It plans to use the rocket again. And on December 21, 2015, California based SpaceX successfully launched a Falcon 9 rocket to space while returning and landing the rocket’s 1st stage to the launch site for a powered, vertical landing. For the first time a rocket has been successfully landed during a commercial satellite launch.

The concepts used by the two companies are very different, as illustrated here:

The end result result of the SpaceX flight is certainly stunning and resembles what science fiction described so many decades ago:

It now remains to be seen if recovering and refurbishing an entire rocket stage and its engines is indeed cheaper than building a new one — something that hasn’t been tried on a commercial scale. But if Wernher von Braun was right (and he usually was), this should be the way to go.

What is the maximum human lifespan? Why do we age? What are the causes and their mechanisms? Why do humans tend to live longer than most other mammals? Do we have a built-in “expiration date” – perhaps for the benefit of the species? Can the aging mechanism be delayed or entirely deactivated leading to eternal life?

What is the maximum human lifespan? Why do we age? What are the causes and their mechanisms? Why do humans tend to live longer than most other mammals? Do we have a built-in “expiration date” – perhaps for the benefit of the species? Can the aging mechanism be delayed or entirely deactivated leading to eternal life?

These and the related questions were what fascinated Dr. L. Stephen Coles, who in 1990 founded the Los Angeles Gerontology Research Group, a global network of researchers and parties intrigued by the boundaries of the human life span. Among the group’s primary work is the cataloguing, tracking and studying of so-called “supercentenarians” – people who live past the age of 110. (As of this writing, there are only 76 such humans verified to be living on this planet. 74 of them are women).

I became intrigued with this subject after reading about Dr. Coles’ work in this Los Angeles Times article in 2004. So I got in touch with him and found a fascinating researcher, inspiring person and mentor.

Subsequently, I wrote a long-form magazine article on the subject, which was published in a German science magazine. Dr. Coles was the most important and primary source for it. During the many hours we spent talking, I learned to appreciate not only his professional knowledge, but also his humor, gregarious personality and boundless enthusiasm for the hope that science would, very soon, make it possible for humans to live exceedingly longer than today.

Steve was a passionate proponent of evidence-based science and rational thought, for the prosperity of all mankind. Sadly, he didn’t get to benefit from the future scientific breakthroughs he was hoping for. I was shocked when shortly after Christmas of 2012, there came an e-mail announcing this Steve’s holidays had been rather miserable.

“I am sad to report that on Christmas Eve (two days ago), I received the

horrible diagnosis of ‘adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas’,” the message read. “BTW, this is the same form of cancer that Steve Jobs CEO of Apple Computer had before he passed away when money was no object. Although I knew that something was wrong with my body for the last three weeks (acute onset of symptoms with the occult tumor possibly growing subclinically for two years or more with no manifestation of its presence until it grew large enough to screw up my internal plumbing by its sheer volume [about the size of a plum])”.

Knowing that pancreatic cancer has one of the lowest survival rates of all carcinomas, the first thing that came to my mind was obvious. It was really crushing.

Of course Steve was perfectly aware of his low odds. He went on writing, “Even in the best of all possible worlds, the mortality statistics after five years of chemo therapy are not great (around 50 percent). Of course, in the event of metastases, one’s life post chemotherapy/radiotherapy are significantly shortened proportionally.”

And unfortunately, there was metastasis in the liver.

Various attempts were made – first surgery (the “Whipple Procedure“), then various chemotherapy, as well as some experimental procedures involving the growth of tumor-specific cells in the laboratory.

While the procedures prolonged Steve’s life to the limits of the statistical prognosis range, they failed in in the end.

When this final message on Oct. 9, 2014, we all knew this was it. “Update on Health Status,” it said. “In order to be eligible for more services, last week I was placed on hospice care at home. Now that I have been taken off taxotere, some measures of health have improved. However, my eligibility for the ECLIPSE clinical trial has been placed on hold pending a decrease in frailty.”

Steve passed away on December 3, 2014, a few weeks short of living for two years after his diagnosis.

But the story does not end here. A few days before his death, Steve must have gone on his life’s final journey: From Los Angeles to Scottsdale, Arizona. Located there is the Alcor Life Extension Foundation – coincidentally also an organization which intrigues me, and about which I have also reported in detail.

Alcor is the leader in “cryonics”. This is an experimental technology which seeks to preserve human bodies through a procedure resulting in suspension of human tissues in liquid nitrogen, at extremely low temperatures, in perpetuity. The hope is that one day in the future, biotechnology will exist to revive these cryogenically “suspended” human bodies, restore them to life by the use of sophisticated nanotechnology, and also deal with whatever the cause of death was.

Depending on the preferences of the customer, either the entire body, the head or just the brain may be frozen (on the theory that once biotechnology has progressed far enough, it should also be possible to either create a new body, or transfer the brain’s content into a computer system).

I am not at all surprised that Steve was also intrigued by the idea and made arrangements to implement this option as a last resort.

And so, Steve’s brain will come to rest in a dewar of liquid nitrogen. Perhaps, one day, he might live again. And he has reportedly made a reservation to attend his colleague Johnny Adams’ 100th birthday party. In the year of 2049.

I will miss him.

Obituary in the Los Angeles Times

I believe Wernher von Braun was completely right when he suggested, in the 1960s, that a manned Mars landing would require nuclear propulsion. (Incidentally, Sergei Korolev, von Braun’s Soviet counterpart, reached the same conclusion). Had the United States Congress implemented von Braun’s suggestions, we would have astronauts on Mars by now — or at least we would have the technical ability for it. Unmanned Mars landers and spacecraft sent to explore the outer planets would also carry much larger scientific payloads.

Unfortunately, a confluence of several factors ended the nuclear space age before it even began. Although there were projects to develop small nuclear reactors, the main impetus didn’t come from NASA, but from the military. The US Navy wanted scaled down power reactors to drive its latest generation of submarines and aircraft carriers. For a while, the US Air Force also studied nuclear propulsion to power long range bombers. Not surprisingly, this idea was abandoned due to safety concerns and after it was realized that ICBMs, not long range bombers, would be the main thrust of nuclear deterrence.

A strong military involvement, and the secretive culture of the Atomic Energy Commission as well as the US nuclear weapons labs, meant that much of the research into small nuclear reactors was highly compartmentalized and classified. Especially during the Cold War, nearly everything containing the word “nuclear” also had a “national security” tag attached.

The secrecy also meant that many of America’s leading scientists and engineers had no access to the most important research papers in the field. This led to a lack of scientific discourse among space experts, few of whom would be pushing for a technology about which they knew no technical details. It also meant that very few political leaders fully understood the potential and necessity of nuclear propulsion in space. In addition, there was the question of which reactor technology to advance. As it happened, the US Navy prevailed in its pursuit of a reactor type suited for marine applications, but ill suited for space travel, where no external cooling medium is available.

Still, as director of Marshal Space Flight Center, von Braun’s word carried weight. Linking together NASA, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), the newly created Space Nuclear Propulsion Office took over the previously launched (and classified) AEC directed Project Rover.

“Project Rover could be divided into three phases: Kiwi, between 1955 and 1964, Phoebus, taking place between 1964 and 1969, and Pewee, taking place between 1969 and the project’s cancellation along with the cancellation of the NERVA rocket at the end of 1972,” writes James Dewar in “To The End Of The Solar System: The Story Of The Nuclear Rocket” (University Press of Kentucky, 2003; Apogee Books, 2008). “Kiwi and Phoebus were large reactors; Pewee 1 and Pewee 2 were much smaller and they conformed to the smaller budget available after 1968. Both Kiwi and Phoebus became part of the NERVA program.”

Many of the papers and background stories relating to all aspects of these programs remain classified and unpublished to this day. At least in part, this could be attributed to self-protective motives of the various entities involved. There is little question that many errors were made in the course of these programs, and that some of them led to serious incidents, mishaps, wasteful spending and questionable decisions.

For instance, in a highly classified test in 1965 at Jackass Flats (an area within the Nevada Test Site), a reactor core was allowed to overheat and explode. The event was recorded by high-speed cameras.

When the reactor blew itself to smithereens, bits and pieces of highly radioactive debris were ejected over 2,600 feet into the sky. Aircraft flew through the debris cloud to take samples. The cloud drifted east at first, then west toward Los Angeles. To this day, the full set of radiation measurement data remains secret.

One minor problem: the test was a violation of the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union. (But one could of course argue that it was merely an “accident”). What goes up, must come down, and radioactive debris rained back down over a wide area.

Five months later, in June of 1965, a nuclear rocket engine code-named “Phoebus” suddenly overheated and exploded. Large chunks of radioactive fuel were ejected, and what was left of the reactor fused into a highly radioactive, hot pile.

Of course, such incidents provided a welcome opportunity to conduct “decontamination exercises”. From whatever can be learned out of declassified documents, the “cleanup process” took 400 people and two months. Almost 50 years later, the entire area around Jackass Flats is strictly off limits to the public.

Were the radioactive fireworks shows necessary? Perhaps, given the circumstances, the knowledge base and needs of the time. But this certainly did nothing to advance the concept of nuclear propulsion for spacecraft. And it did not exactly alleviate the fears of taxpayers that such programs tend to be out of control, over budget, irresponsible, lacking oversight, and of questionable value to the public. As a result, politicians generally find it difficult to justify and back such programs before the public, which is why they often can only exist in secret. In turn, this creates a hopeless feedback loop.

Despite its problems, NERVA was considered widely successful in achieving its technical objectives. But in the end, it was killed when the funding spigot closed off the flow of cash.

In a first blow, the incoming Nixon administration slashed NASA’s budget dramatically. The remaining Apollo moon landings were canceled, even though the hardware for them had already been built and all personnel and infrastructure were in place. Worse: the new administration and others in NASA’s leadership maneuvered von Braun into a rather innocuous desk job. In plain terms, he was pushed aside by internal power struggles. Overruling his objections, NASA decided to cancel the entire Saturn rocket program — a decision I consider to be the worst blunder in the entire history of human spaceflight.

Now lacking a large launch vehicle to lift large payloads to Earth orbit, there was no more way to the Moon or beyond, and there was no way to launch a nuclear-propelled spacecraft to Mars or elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union (and later, Russia) pursued a more steady course with its TOPAZ and ENISY reactors — although the objectives were different from NERVA. The most important objective behind these Soviet programs was the generation of electricity, not thrust. The US had, and probably still has, similar secret programs to develop small reactors for powering spacecraft.

What is publicly known is that the Soviets flew some of their systems in space on a large scale — with rather mixed results. There is less public information about US reactors flown in space. On April 3, 1965, SNAP-10A was launched from Vandenberg AFB in California into an unusual, retrograde orbit. After 43 days, a voltage regulator aboard the satellite failed, and the reactor was shut down. The satellite was left in a 1300 km high orbit. It is of some concern, because it has shed debris after some event — possibly a collision or meteorite hit — in 1979.

As part of Upravlyaemy Sputnik Aktivnyj (Russian: Управляемый Спутник Активный), or US-A, the Soviets launched 33 reactors aboard Earth-observing radar satellites in low Earth orbit. In addition, the Soviets are known to have launched at least two larger (6 kW) TOPAZ reactors aboard their Kosmos 1818 and Kosmos 1867 satellites.

Russian satellites were generally designed to either eject their radioactive components, or boost the entire satellite, into a “safe” storage orbit further away from Earth. To make a long story short: the reliability record of this technique has been abysmal. In quite a few cases, radioactive debris was either lost in orbit or re-entered the atmosphere. In some instances, radioactive debris fell back to Earth.

This brings me to a question often asked: isn’t it generally extremely dangerous to strap a nuclear reactor on a gigantic, possibly malfunctioning rocket? The answer is a little complex and could fill a book.

In simple terms, here is what I believe: when used for interplanetary travel (as opposed to use in near Earth orbit), the risks are quite manageable. As Wernher von Braun suggested, a reactor for spacecraft propulsion would be sent to orbit “cold”, on a conventional rocket. In this first stage of the trip, the reactor fuel would be tucked away in a strong safety container. Only when the spacecraft is at a safe distance from Earth would the reactor be made operational and start up for the first time. It is only then when the most dangerous, radioactive results of the fission reaction are produced.

After its initiation, the reactor core would remain in space and never return to Earth. However, by sending it on a return orbit around the Sun, it would even be possible to reuse it for multiple missions, for example to “cycle” spacecraft from Mars to Earth and back. (Buzz Aldrin has been fervently advocating one such concept, the “Aldrin Cycler”).

The arithmetics for a manned mission to Mars have not changed since von Braun’s time. As he pointed out, relying on chemical fuel for the interplanetary journey soon becomes a case of diminishing returns. The reason is that it takes a huge amount of rocket fuel to get the payload on course to Mars in the first place. The longer the journey takes, the heavier the load of supplies to be carried for the astronauts. And on the return trip, more fuel is needed, the weight of which has to be figured into the total mass of the outward bound mass.

By means of its very high power-to-weight ratio, a nuclear reactor can reduce the mass to be transported to and from Mars by a significant amount. And it might be possible to speed up the trip, so that fewer supplies and less shielding against cosmic radiation are necessary.

So where do we stand?

Electricity generating, small nuclear reactors like the Russian TOPAZ could be used as part of a propulsion system, possibly employing some type of ion engine. Perhaps these could even be scaled up to a certain degree. But since ion engines provide only low (yet steady) thrust, they are best suited for unmanned spacecraft in which travel time is not as important a factor.

Los Alamos National Laboratory has recently introduced a clever, innovative nuclear power generator for spacecraft:

An interesting idea, but again: even scaled up, this is still a low-power concept.

For serious human travel to Mars and beyond, a much more powerful reactor and propulsion system would be needed — something similar to NERVA. And this is just what von Braun already knew 50 years ago. Trying to make plans to land humans on Mars without an available nuclear propulsion system amounts to putting the cart before the horse.

If you have questions or information about this subject, or if you would like me to write about it for a commercial publication, please e-mail me.

Links:

NERVA: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NERVA

AEC paper on NERVA:

http://archive.org/details/nasa_techdoc_19790076129

TOPAZ: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TOPAZ_nuclear_reactor

Mars Cycler: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mars_cycler

LANL Small Nuclear Reactor:

http://www.lanl.gov/newsroom/news-releases/2012/November/11.26-space-travel.php

A Russian computer security firm got a lot of publicity this week after they announced that about 600,000 Macintosh computers allegedly have been infected with a malware called “Flashback”. Of course, MacOS malware is quite rare, so the news spread like wildfire. It is not quite known what Flashback will lead to, but at this point, there’s no reason to panic.

A couple of points: Flashback is not a OS-level attack on the Mac. (To this date, no such thing has ever been successful in MacOS, and Apple Macintosh computers remain the most secure personal computing platform available to consumers).

Instead of attacking MacOS, Flashback exploits a weakness in Java, a programming language developed by Sun Microsystems (now Oracle Corporation). It uses this weakness to disable some of the Mac’s security features. For various reasons, Apple has supported Java (more or less grudgingly), but viewed it as an (outdated) liability for some time now. Apple finally dropped Java support with the current version of the MacOS (OSX 7 or “Lion”). In its current version of the MacOS (OSX 7 or “Lion”), Apple no longer includes Java in the standard installation. However, users are still able to install and run Java if they wish. (Note: Java, the programming language is not the same as “Java Scripts”, which are a component of many web sites).

Although Apple’s latest operating system does not even support does not install Java by default any longer, many Mac users still have vulnerable Java versions installed, and are therefore vulnerable. But even so, Flashback can only install itself on the user account active at the time of infection. It cannot spread throughout the entire operating system.

At a meeting yesterday, certified Apple Certified Support Professional and consultant, Benjamin Levy (Solutions Consulting) questioned how widespread Flashback really is. So far, he says, there have been almost no reports of infections on the Apple Consultants Network. Levy noted that the claim of “600,000 infected machines” originated with a Russian company selling security software.

How big is the risk? So what should be be done?

Benjamin Levy: “From what is known at this point, the threat from this malware is low. And if you want to go back to the Symantec website for confirmation, it lists Flashback as Risk Level 1: Very Low.”

“I am certain that in the weeks to come this malware will be fully dissected and we’ll know a great deal more about what it does, but for now I think reasonable caution is about all I would recommend. Check to see if you have it, remove it if you do. Learn from the experience and be vigilant about keeping your systems up to date. And yes, this means not letting your computers age outside of current versions of the OS.”

In summary: If you are using Apple’s latest OS (Lion) and have not installed Java, you are fine. If not, make sure you have the latest Java version installed.

If you want to check if your system has been infected, there are various options. Consultant Bruce Gerson (BSG Solutions) recommends:

Or, you could download and run a simple script developed by Bart Busshots:

http://www.bartbusschots.ie/blog/?p=2236

(I have personally tested this script. It ran fine).

Even if you have the malware, this does not necessarily mean it it working, Gerson points out. (Using the FlashbackCheck.com website will determine if you are part of the botnet).

If you want to wait, Apple will be releasing a removal tool:

http://support.apple.com/kb/HT5244?viewlocale=en_US&locale=en_US

(Thanks to Bruce Gerson, Ben Levy, Garry Margolis, LAPUG.org, Bart Busschots).

So this is apparently the new Windows 8 Metro start screen (for mobile devices, but also for the computer desktop).

Apart from the dull and dated 1990s look and the clashing colors, how is one supposed to read the tiny lettering on the control surfaces?

Did Microsoft outsource their design to India? Are they kidding? They want to compete against Apple’s iOS 5 and Android with this??

I almost feel bad for them. I was hoping that Microsoft would come up with something serious, because I believe Apple must have competition to thrive. (Android hardly counts, because Apple users won’t even consider touching it with a pole).

If this is all Microsoft is still able to cook up, I am afraid they are done.