To say that Hemingway was prone to injurious brushes with death would be an understatement. In WW-1, he was nearly killed by a mortar blast in Italy. (He had just returned from the canteen and from bringing chocolate and cigarettes for the men at the front line). His shrapnel injuries sent him to the hospital for six months. Then, during WW-2, a German anti-tank round blew him from the sidecar of a motorbike, hurling his head into a rock. In a 1945 a car accident he “smashed his knee” and sustained another “deep wound on his forehead” (along with a concussion), which was followed by another car crash in 1947. And so it continues.

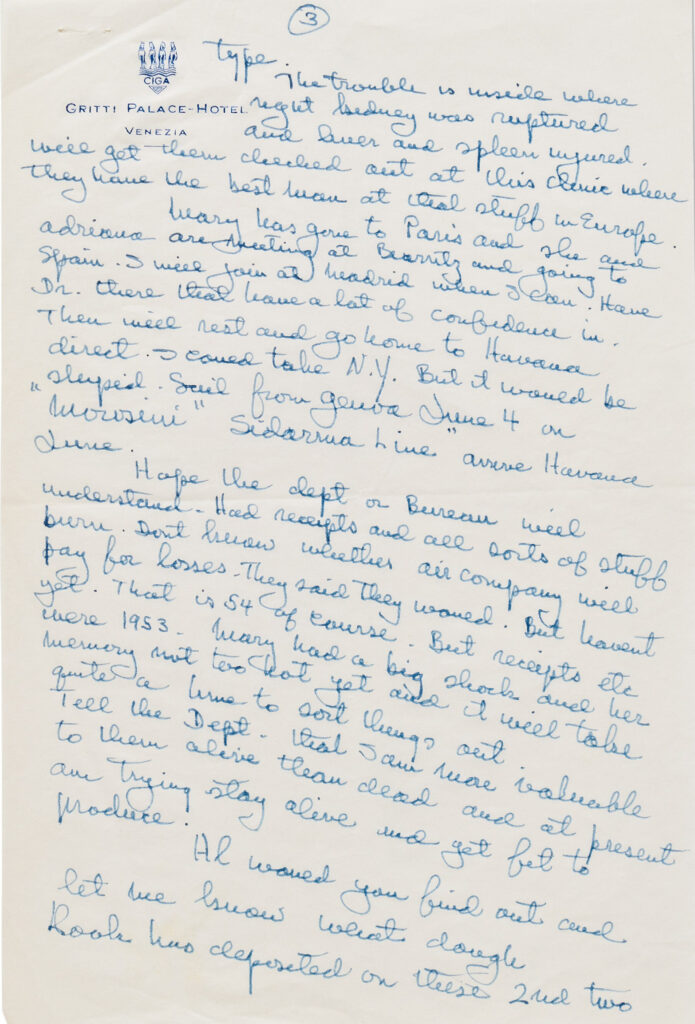

In January 1954, while in Africa, Hemingway was almost fatally injured in two successive plane crashes. During a flight over the Belgian Congo, the chartered plane struck a utility pole and went down in heavy brush. Hemingway’s injuries included a head wound. His wife Mary, also on board, broke two ribs. A pilot who passed over the wreckage spotted no survivors. A report went out saying the famous American author was dead.

In fact, Hemingway, his wife, and the pilot had escaped from the wreck and were camped in the brush nearby, surrounded by a herd of elephants, and eventually rescued by a tourist boat.

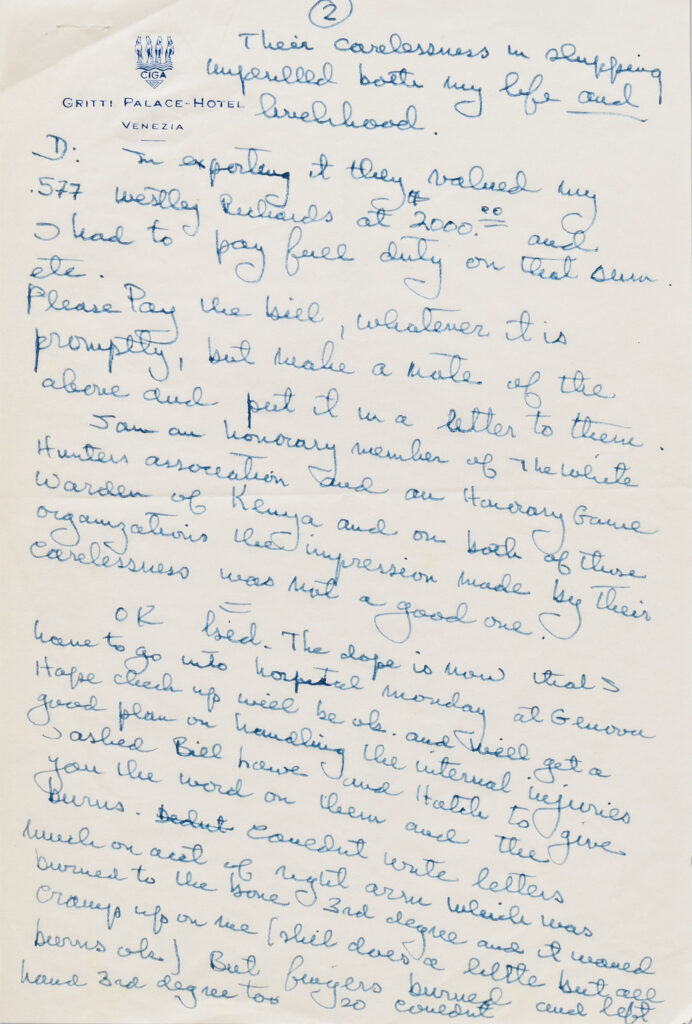

The next day, the couple boarded another plane to get medical care in Entebbe, Uganda. But the aircraft caught fire, crashing during take-off. In the second crash, and while escaping from the wreck, Hemingway suffered burns and yet another concussion, the head injury being serious enough to cause a leakage of cerebral fluid.

Hemingway made light of it when he and his wife finally arrived in Uganda (this time by car), carrying a bunch of bananas and a bottle of gin.

Despite suffering from his severe injuries, Hemingway proceeded to go on a fishing trip with his wife and son. This time he got caught in a brushfire. Again he was injured, sustaining second-degree burns on his lips, legs, front torso, left hand, and right forearm.

Months later in Venice, Italy, Hemingway’s wife recounted the extent of the damage to friends: two cracked discs, a kidney and liver rupture, a dislocated shoulder and a broken skull.

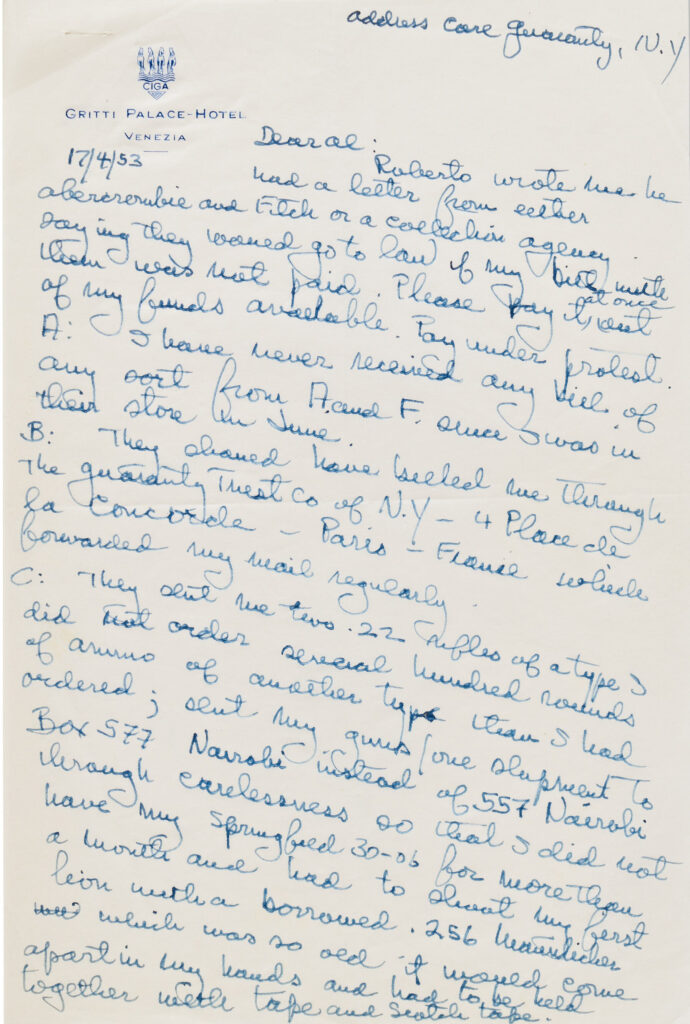

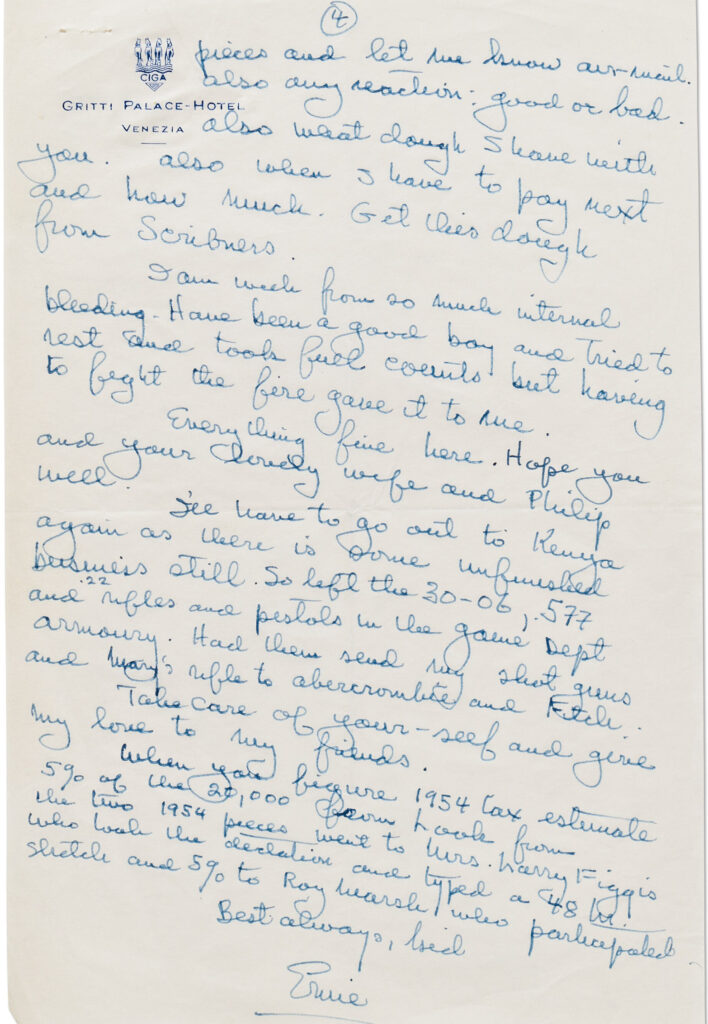

Now, a handwritten letter from Hemingway to his lawyer has re-surfaced, and was sold at Nate D Sanders Auctions in Los Angeles. Dated April 17, 1953 (which is an error – it was 1954), and written on paper from the Gritti Palace Hotel in Venice, Italy, Hemingway’s own writing gives a glimpse of the events as he saw them.