Today is the birthday of one of my heroes, Charles Lindbergh: aviation pioneer, author, inventor, world traveler, explorer, environmentalist, intelligence agent, social and political activist, philanderer and — toward the end of his life — hermit and recluse.

For most people alive today, the extent of fame and admiration heaped upon Lindbergh during his lifetime is hard to appreciate. After his transatlantic flight in 1927, practically every man, woman and child in America and Europe knew his name. (Contrary to what many people think, Lindbergh was not the first person to cross the Atlantic by plane. He was the first person to fly non-stop from New York to Paris).

Lindbergh was a complicated, multifaceted and controversial man of many secrets. On the one hand, he neither cared for party politics nor for politicians. On the other hand, he was an American isolationist, a strong supporter of the America First movement who prominently advocated a neutral American foreign policy — as opposed to a military engagement in Europe.

To underline his views before World War II, Lindbergh expressed admiration for the German Nazi party. To be more precise: Many years before the Holocaust and Nazi brutality during the subsequent war became known, Lindbergh expressed admiration for the rapid progress the German people were making at the time.

While America was only slowly (if at all) recovering from the Great Depression, Hitler’s regime, almost overnight, eliminated corruption, inflation and unemployment. After suffering from many years of disastrous economic conditions, the German people seemed to be doing better each year. The Reich was making huge advances in science and technology, the aviation sector being of particular interest to Lindbergh.

Lindbergh’s assessment of the strategic situation in pre-war Europe was that if Britain and France attempted to answer Hitler’s provocations with military power — without first building up its military aviation sector — both countries would fare very badly against the more modern Nazi forces. (Lindbergh’s analysis was shared by many high ranking military officers in France, Britain and in the United States. In hindsight, we know that Lindbergh’s assessment of the Luftwaffe’s strength before the war was perhaps a little exaggerated, but fundamentally correct).

Back in America after living in Europe (and touring Nazi Germany), Lindbergh became active as an influential spokesperson for groups lamenting America’s drift toward war. During these politically charged times, the American pro-war propaganda machine began to loudly denounce Lindbergh as a Nazi-sympathizer and anti-Semite. (I believe he has neither, but more likely the victim of a campaign to ruin his character and undermine his influence as an opinion leader who had proven to be quite capable of rallying the masses).

To understand this, one must comprehend the historical context. After WW-I, the stock market crash in 1929, and the resulting Great Depression the average American had very little appetite for another war in Europe. Truth be told, there were quite a few Americans who looked with a certain amount of admiration at how the German Reich’s new leadership was improving the horrendous economic problems of the German people practically overnight. In the process, the Nazi party had also wiped out the once very powerful German communist party and prevented a bolshevik Germany — a fact that did not escape American anti-communists.

Lindbergh (and many other Americans at the time) thought that a strong Reich would keep Stalin’s Soviet Union under control, thereby making American involvement unnecessary and unwise.

Even after the Third Reich’s quick victory against Poland in 1939, the vast majority of the American people remained “non-interventionists”, who wanted no part in the brewing European conflict. Opposed to them were the “interventionists”, who believed that Hitler had to be stopped at all cost, even if it meant going to an all-out war in Europe.

Lindbergh argued that the United States was in a virtually impregnable position. Not only did Nazi Germany have no strategic ability to invade or harm the US homeland, it had shown no attempt whatsoever to develop military capability that could threaten America. Lindbergh proclaimed that when interventionists said “the defense of England” they really meant “defeat of Germany.” The non-interventionists also accused American industrialists of having purely financial motives for driving America to war.

The political tensions and attacks on Lindbergh boiled over after a speech he delivered to a rally in Des Moines, Iowa on September 11, 1941. In that speech he identified the forces pulling America into the war as “the British, the Roosevelt administration, and the Jews”. While he expressed sympathy for the plight of the Jews in Germany, he argued that America’s entry into the war would serve them little better. Lindbergh said, in part:

It is not difficult to understand why Jewish people desire the overthrow of Nazi Germany. The persecution they suffered in Germany would be sufficient to make bitter enemies of any race. No person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution the Jewish race suffered in Germany. But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy, both for us and for them.

Instead of agitating for war the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way, for they will be among the first to feel its consequences. Tolerance is a virtue that depends upon peace and strength. History shows that it cannot survive war and devastation. A few farsighted Jewish people realize this and stand opposed to intervention. But the majority still do not. Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government.

[Wayne S. Cole, America First: The Battle against Intervention, 1940-41 (1953)]

These remarks must be seen in the political context, and in view of the fact that Lindbergh, all his life, was a staunch and principled pragmatist who approached every problem with unemotional analysis.

Before the war, Lindbergh (who after the war expressed great disgust after learning of the extent of the Holocaust) held the view that if Hitler’s Third Reich and Stalin’s Soviet Union were left alone with each other, they would sooner or later smash each other to pieces — without the sacrifice of American lives, and without a global war. Had this come to fruition, one might argue that America would have been spared around 200,000 fatalities in the European theater. And since Nazi Germany would have wiped out or at least seriously decimated the Soviet Union, the whole Cold War, the nuclear arms race and all its global consequences would never have happened.

Lindbergh’s views were quite popular before the war and made a lot of sense when seen from the perspective of the 1930s.

As for the Holocaust: Although the US was already engaged by supporting Nazi Germany’s enemies financially and with massive arms shipments earlier, the United States and Germany officially did not go to war until 1941. Only two months later, on January 20, 1942, at the secret Wannsee Conference, the Nazi leadership, now overburdened by heavy losses in the campaign against the Soviet Union, supply shortages as a result of the British fleet’s campaign, and America now joining the war officially, decided to implement the “Final Solution” – the annihilation of all Jews under the Reich’s control.

The question of whether the US military engagement in Europe (as well as other American policies and military strategy) accelerated, was a contributary factor, or perhaps even one of the culpable causes of the steady escalation of Nazi brutalities during the war is one of the politically most intensely charged subjects in all of history, and remains so even today.

But back to Lindbergh:

When America was attacked at Pearl Harbor, Lindbergh changed his anti-war stance overnight. Now he felt that his country needed his skills. But at that time, the Roosevelt administration and J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI had practically declared him an enemy of the state. As a consequence, the US military rebuffed Lindbergh’s offer to go on active duty and fight for his country.

But Lindbergh was not to be deterred. He joined the war effort in the Pacific as a civilian and flew more than 50 combat missions in support of the US Marine Corps and the US Army Air Force (the predecessor of today’s US Air Force). In addition, Lindbergh’s work as a pilot trainer and consultant made tremendous contributions to tactics, procedures and technology in American military aviation.

Long after Lindbergh’s death, it was discovered that he had a secret family in Germany (as well as several mistresses), which he successfully kept a secret from both the press as well as his American relationships.

Lindbergh may have been a man of many flaws, but one of even greater virtues, a man who spent his life unafraid of traveling over rough and rugged roads, toward the unknown, and daring to fly even the stormy skies.

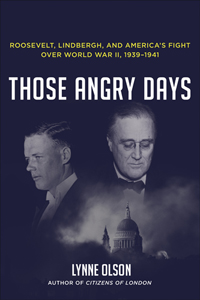

Recommended reading:

A Scott Berg: “Lindbergh”. First published in 1998 (now in paperback)

Lynne Olson: “Those Angry Days – Roosevelt, Lindbergh, and America’s Fight over World War II, 1939-1941”. Published 2013. ISBN-13: 978-1400069743.