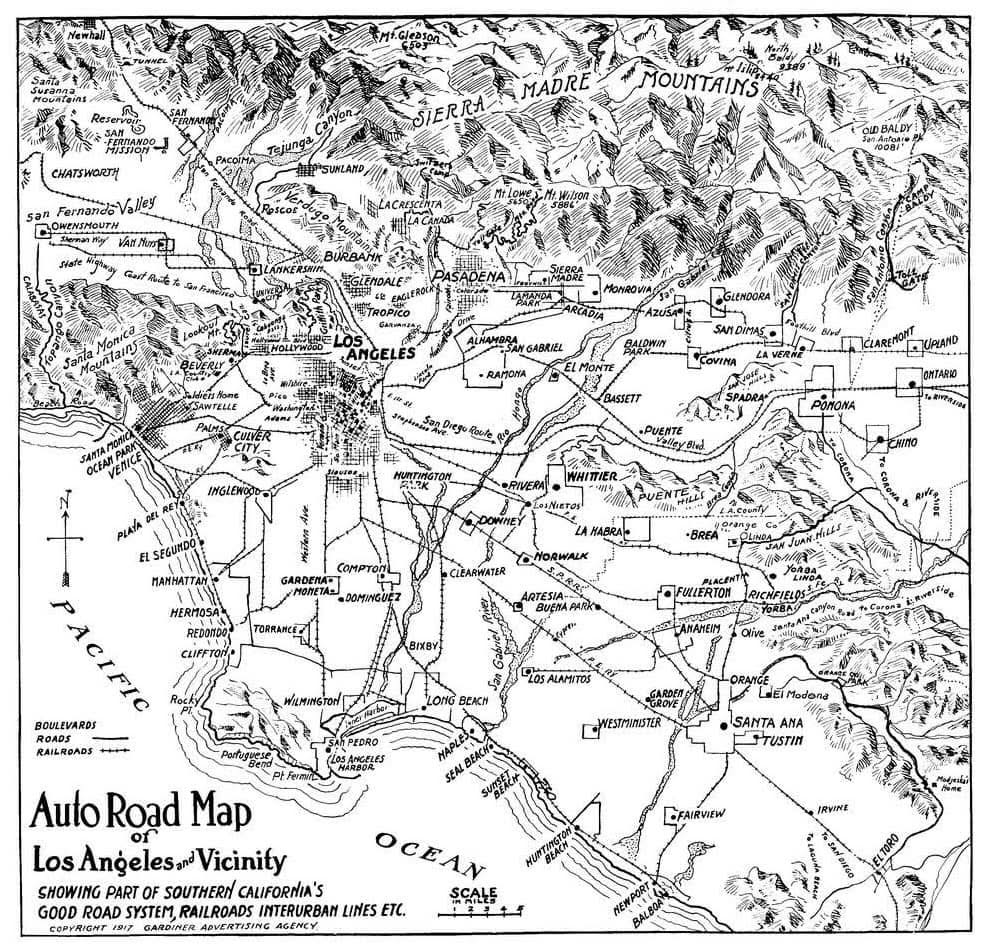

At the time this map was printed, Los Angeles County was booming with droves of new arrivals pouring in mostly from the East Coast. According to the U.S. Census, the county’s population had grown by 196% during the decade following 1900. By 1910, it had reached 504,131.

At the following census in 1920, the county’s population had swelled to 936,455, which translates to another 85.8% increase over 10 years . Within 20 years of 1900, the population had increased by 5 1/2 times, and 13 times by 1930, ending the decade with a total population of 2,208,492.

Most of the new settlers arrived by railroad. But when the above map was printed, the first automobile affordable to middle-class Americans, the Ford Model T was already in its 9th year of production. While there was a frenzy to build electric tram lines and a bus infrastructure connecting the Los Angeles area, people’s preferences, and the future of personal transportation, were clear. Then as now, people preferred private automobiles over communally shared vehicles the same way as they prefer private bathrooms over public toilets. For much the same reasons, they always will.

By the end of production in 1927, Ford had sold 14,689,525 Model Ts, with the least expensive model selling for just $260. (At the time of this writing, this would amount to an inflation-adjusted price of roughly $5,000 in 2025).

Motoring at the time would have been both fun as well as challenging. Many Los Angeles area roads at the time were still unpaved and rural. The various towns, settlements and cities were scattered about the vast county, and surrounded by farm or ranch land. Cars frequently broke down miles from populated areas. Flat tires were common. The quality of gasoline was unsteady and questionable, and filling stations were a novelty.

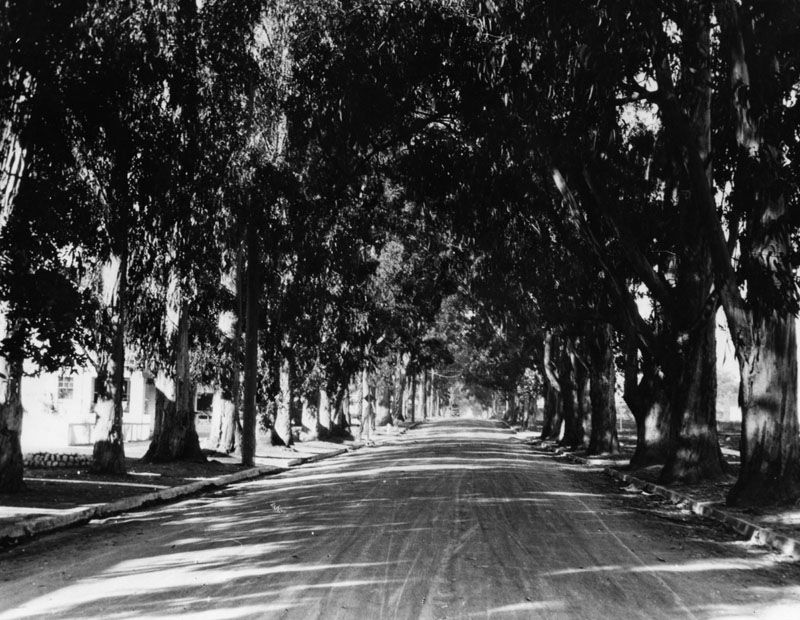

Melrose Avenue, 1910

Most gasoline pumps were installed in front of hardware stores, feed companies, livery stables, and a variety of other retailers. Service Town, the earliest known gas station in a modern sense, was built in 1914, three miles from downtown Los Angeles. Before that time, motorists went one place for gas and oil, and other places for lubrication and cleaning, for repairs, or for tires and other accessories.

As automobile sales increased, the demand for fuel led to a more systematic and standardized way of delivering it. In 1914, Standard Oil of California opened a chain of 34 homogeneous stations along the West Coast, and other oil companies quickly followed suit to secure an outlet for their now increasingly branded and advertised products.

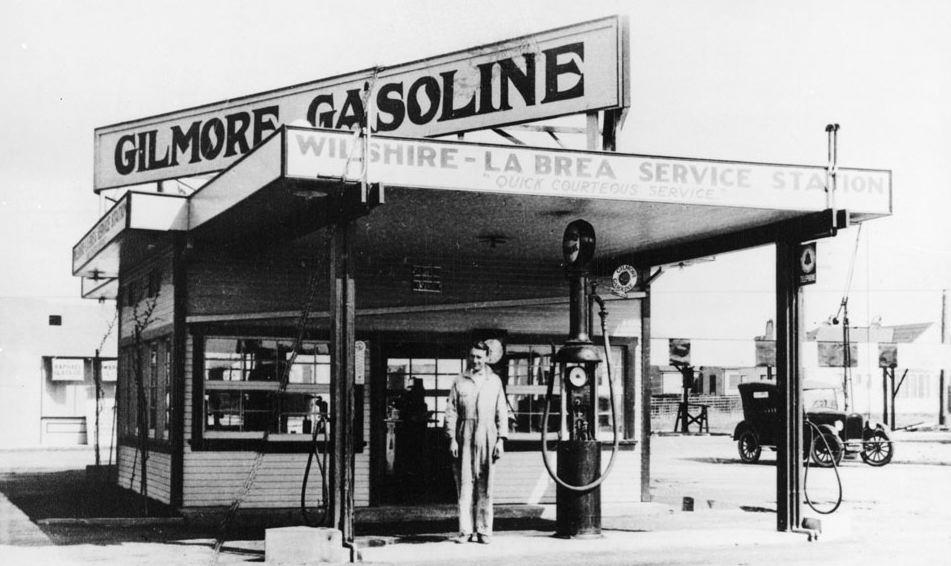

The Gilmore Gas Station was one of the first gas stations in Los Angeles. It was located on the northeast corner of La Brea and Wilshire Boulevards. Photo from ca. 1920. (Los Angeles Department of Water and Power).

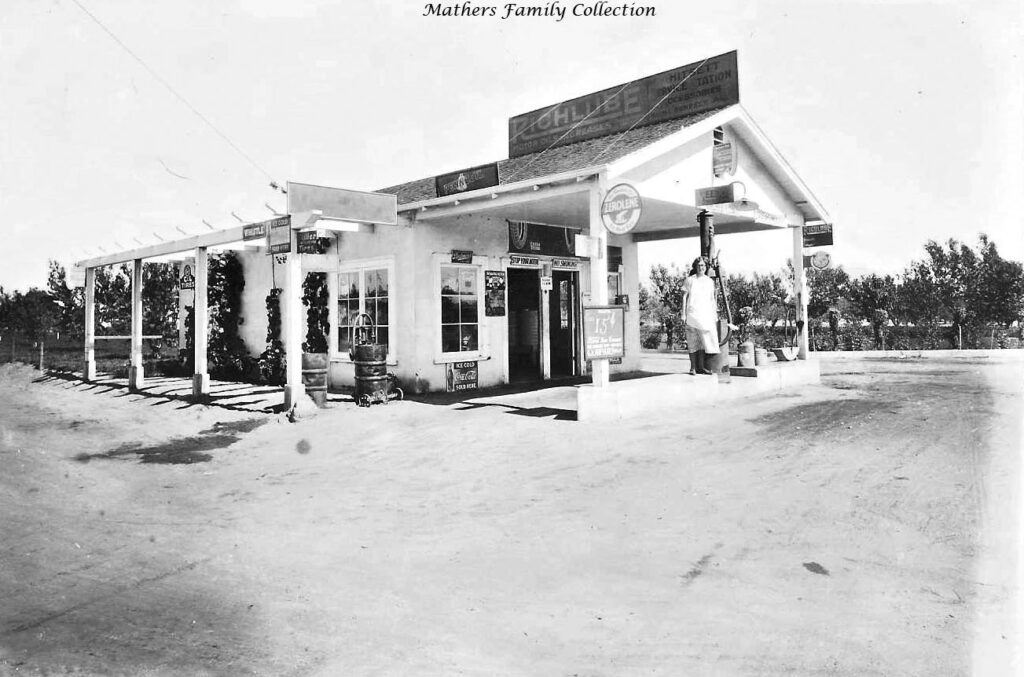

View showing Mabel Demspey standing on the gas pump island at the Whitsett Service Station located at 2912 Whitsett Avenue in North Hollywood. Photo from 1923. (Los Angeles Department of Water and Power).

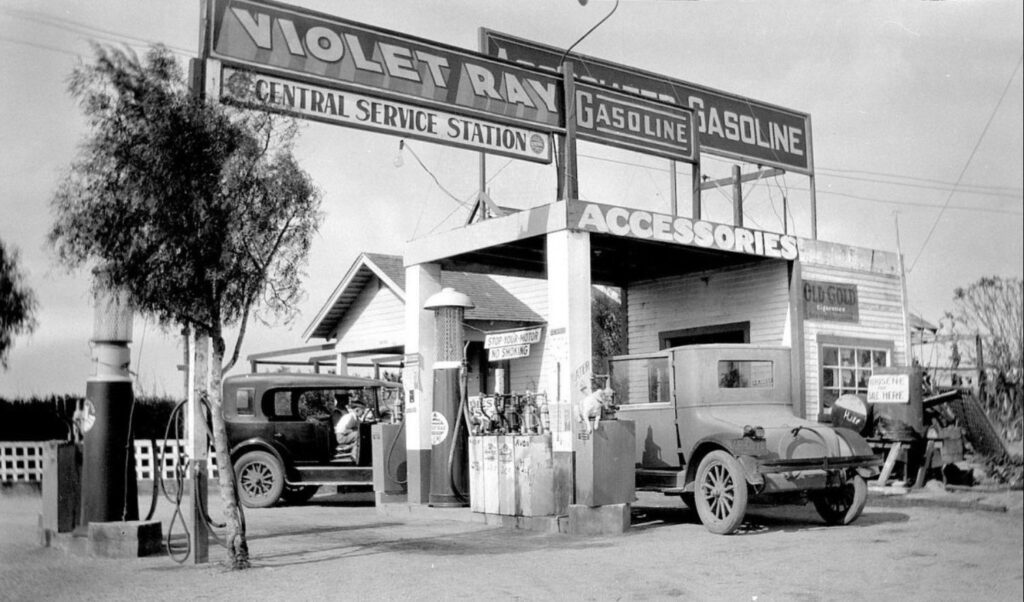

A man and boy sit in a car at the Central Service Station which is selling both Violet Ray Gasoline and Associated Gasoline. Note the dog sitting on top of what appears to be an oil dispenser. Photo ca. 1928. (Los Angeles Department of Water and Power).

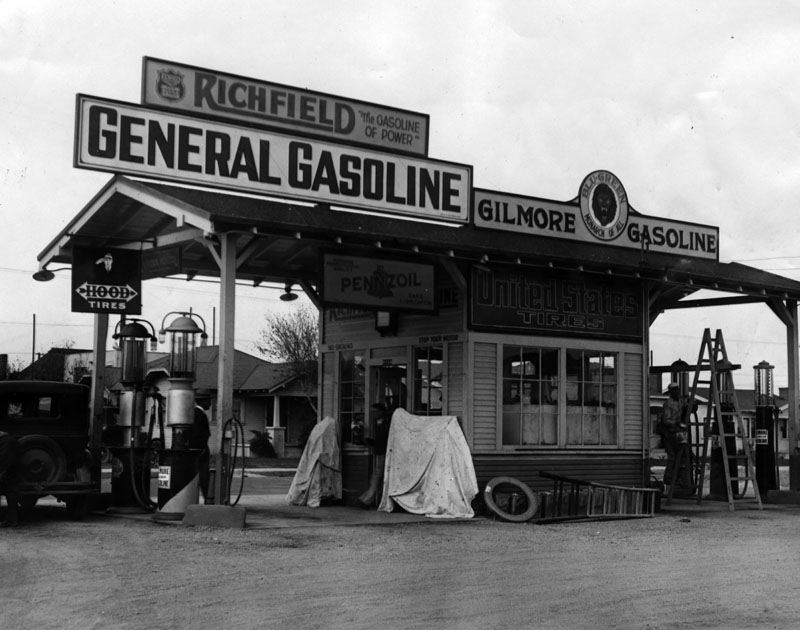

View of service station with gas pumps on either side located at 1800 1/2 Long Beach Boulevard, South Gate. The signs advertise General Gasoline, Richfield Gasoline, Gilmore Gasoline, Hood Tires, United States Tires and Pennzoil. On the right, an attendant is climbing a ladder. Photo ca. 1928. (Los Angeles Department of Water and Power).

Some of the cities on the road map shown above no longer exist, but were absorbed by Los Angeles or other cities. Examples (on the Westside) are the historic City of Sawtelle and the town of Venice, which were annexed by the City of Los Angeles, and the City of Ocean Park, which opted to join the City of Santa Monica

In 1910, the semi-rural town of Hollywood had voted to merge with Los Angeles in order to secure an adequate water supply and to gain access to the L.A. sewer system. This was very common development at the time, and one which many cities later bitterly regretted.

The community of Pacific Palisades, which was consumed by the horrendous fire of 2025, didn’t exist yet. Neither did the City of Malibu, nor the Roosevelt Highway (later renamed to “Pacific Coast Highway”). But there was a “Beach Road” along the coast, as well as a steam rail line from Downtown Los Angeles to Santa Monica. The latter was how most beach goers arrived to take a few days of respite from the summer heat further inland.

By 1912, some motion-picture companies had moved out West to set up production facilities near or in Los Angeles, one of the first one being short lived Nestor Studios. (Originally known as Nestor Motion Picture Company, then Nestor Film Company, it merged with the Universal Film Manufacturing Company, headed by Carl Laemmle, in 1912).

At the time, the pioneering movie studios were still a newfangled and rather suspect industry, viewed with skepticism by investors, polite society, and cultural guardians alike. They certainly weren’t the main reason why people from all over North America (and Europe) wanted to move to Los Angeles. More important factors were the discovery of vast oilfields and seemingly endless opportunities to make money and fortunes. There was affordable and available vacant land on which one could build quickly, cheaply, and year-round. And all this came with a pleasant climate, and a plentiful supply of fresh meat, fruit and vegetables throughout the year. (This would have been a major draw at a time when heating consisted of building a fire in an oven or fireplace, and electric refrigerators were a rare novelty).

But I would argue that of all industries, it was the motion picture industry which drove America’s rapid motorization in the first part of the 20th Century. Cinemas would soon reach every corner of the country. And there, on big silver screens, huge crowds of people saw all segments of society happily motoring around Southern California. Often in open cars no less, far from snow and ice, and enjoying the joys of personal, individual transportation. To audiences back then, all this looked like magic. And of course, the car industry back east could not have invented a better publicity campaign.